Interview With Lawrence Davies - Author of 'Mountain Fighters - Lost Tales of Welsh Boxing'

By AmeriCymru, 2012-07-03

AmeriCymru: Hi Lawrence and many thanks for agreeing to be interviewed by AmeriCymru. When did you first become interested in boxing and in particular Welsh boxing?

AmeriCymru: Hi Lawrence and many thanks for agreeing to be interviewed by AmeriCymru. When did you first become interested in boxing and in particular Welsh boxing?

Lawrence: Hi Ceri, great to hear from you, its a real pleasure to be asked. I guess like most boxing fans I have fond memories from tuning in and watching fights sitting on the rug next to my dad as a kid, who has always enjoyed the boxing. Saturdays it was always wrestling on ITV in the afternoon and a fight in the evening, maybe a bit of Fit Finlay or Kendo Nagasaki after lunch followed by some Bruno, Benn, Eubank or Tyson with a bag of Frazzles. Happy days !

I grew up in Cardiff, where everyone knows the name of Jim Driscoll, even if they arent familiar with his story. They called him Peerless Jim for his boxing skill, but it was really his kindness and charity that cemented his name in Welsh sporting history. He was the first British boxer to win the Lonsdale featherweight title belt and gave up the opportunity to fight for the championship of the world in the US as he had given his word he would fight on a fundraiser for the Nazareth House Orphanage in Cardiff and returned home. It has been estimated that up to 100,000 people lined the streets of Cardiff when he died, which would make it the largest funeral in Welsh history.

The orphans of Nazareth House made up a large number of the mourners, and there were countless famous hard men of the ring weeping among them, friends and opponents alike. It struck me as the strangest contrast, that a man who spent his life in one of the toughest professions there is had such a kind heart when it came to his own people. He gave a lot of money to the poor and needy, and boxed thousands of rounds to raise funds for those less fortunate than himself. He became a true peoples champion in Cardiff, and was one of the most admired champions in British boxing, as much for his actions outside the ring as within it. I think he must have been a remarkable man, and like all the greatest boxing stories, Jims story really transcends the sport. Inspirational and heroic in a way I think we rarely glimpse in boxing today. There is a statue to Jim and his achievements in Cardiff city centre.

(Click the image below for video footage of Peerless Jim Driscoll's funeral: Ed)

As I got older I followed the careers of local boxing stars made good like Steve Robinson and Joe Calzaghe. Steve followed in Driscolls footsteps and became featherweight champion, and obviously Joe will long be remembered after retiring undefeated. One of my fondest memories was being at ringside years ago for the Calzaghe Brewer fight. I was working in a warehouse at the time, and I was probably living off beans on toast for a month afterwards, but it was a hell of a battle and worth every last depressing baked bean.

Over the years I read quite a bit about the first boxing greats to come out of Wales. What was fascinating to me was that all of their stories are so intriguing in their own right, and I was surprised to find that so many of the early Welsh fighters had been forgotten. Even more interesting to me that their careers started at the end of an earlier fighting tradition, where the fist fighters had been known as mountain fighters, before modern boxing had really taken off in Wales. Fist-fighting or prize fighting was illegal, so most fights happened outside the reach of the law, on the mountains above the towns of the South Wales valleys and were scheduled to start at dawn to avoid the police, in areas called bloody spots or blood hollows where they did battle with the raw uns, meaning that these were all bare-knuckle battles. Although it was an underground sport, it was incredibly popular even though its brutality meant that many of the men died on the mountains due to their injuries, every town and village had its local champ. A fight continued until a man was knocked unconscious or was unable to continue. As the fights could often go on for hours and there were unlimited numbers of rounds that only stopped when a man went down, the men that fought were often left hideously disfigured. Broken teeth and smashed up faces became the badge of the mountain fighters. In a sense they were almost like unarmed gladiators of early Welsh boxing.

In a strange twist, the boxing rules on which modern boxing were based had been drafted in 1865, and were also written by a Welshman from Llanelli, named John Graham Chambers. The rules were named after his friend, the Marquess of Queensberry, in an attempt to lend a degree of respectability to the sport and also distance boxing from the horrors of the old prize-ring and showcase scientific boxing skill as opposed to a bloody mauling. The new rules didnt automatically take hold in Wales, as the knuckles were the time honoured way of settling disputes, although a few early showmen were promoting contests wearing gloves. Boxing booths, little more than travelling tents with a string of boxers demonstrated their skills on fairgrounds and accepted challenges from the audience. If they were skillful or lucky enough to last a set number of rounds they could claim the showmans cash prize.

The showman would charge a fee for entry, and some did particularly well out of the trade and became celebrities in their own right, people like William Samuels and Patsy Perkins. Many of the knuckle men were quite resentful of the booth boxers and would often turn up on the fairground to try and further their reputations by mauling and battering them.

Despite this, the booth was a very effective training school for boxers. Many would say that there hasnt been a better system for making boxing champions since. Most of them fought multiple times each showing, so by the time they might be termed professional boxers, they might have met hundreds of opponents. In Wales the booths did a roaring trade, and virtually all the old British champions came out of them. I find it astonishing that the first three Lonsdale belt winners were all Welsh, two had come via the booths, and all were competing in a sport where the modern game had developed on rules had also been drawn up by a Welshman. One of the longest running booths was Ron Taylors, which was actually still touring the country until just a few years ago.

Although I came across a couple of notorious characters of this time that had been mentioned in passing in romanticized works of historical fiction, I found very little solid documentary information about them. It seemed to be a very interesting period in Welsh history that was mostly forgotten or merely alluded to, so I decided to look into it myself.

AmeriCymru: What inspired you to write 'Mountain Fighters - Lost Tales Of Welsh Boxing'?

Lawrence: As a teenager Id occasionally drop in for a pint at the Royal Oak in Newport Road if they had a decent band on. The great guitarist Tich Gwilym used to play there back in the day. It was stuffed with photos and pictures of Jim Driscoll back then and Id have a look over them while nursing a pint. Jim was instantly recognizable, and all the others in the pictures were a mostly unnamed or unknown clump of tough looking old bruisers with squashed noses and cauliflower ears. It struck me that in boxing, the greatest part of the story is often forgotten. We remember the champion, and not necessarily the men that he beat to get there. If Driscoll and Jimmy Wilde and all the others had become champions, who did they beat? I thought there must have been some fairly established fighters knocking about to have even paved the way. I figured that some of their stories should be remembered. I didnt get round to it straight off, but the thought remained.

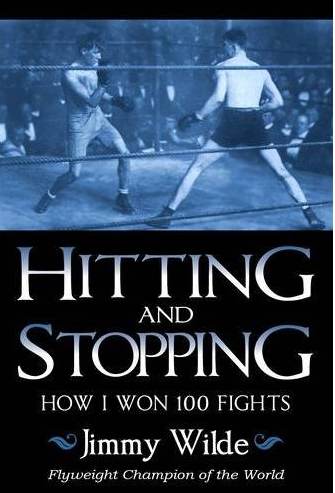

My family are from Merthyr and my uncle once met the immortal Jimmy Wilde, who is usually recorded as having been born in Tylorstown, but was actually born near Merthyr at Quakers Yard. He became flyweight champion of the world in 1916. Wilde fought hundreds of times, frequently giving away stones in weight. He remains one of the greatest marvels in boxing. Apparently, even Jimmy used to sit agog hearing the tales of his mountain fighting father-in-law Dai Davies of Tylorstown, who wasnt adverse to a bare knuckle fight for hours on end, probably more often than not for a jug of ale as a prize. Unbelievable. Today theres not many people outside boxing circles that even remember Jimmys name, which is something bordering on sacrilege. Sadly there is no statue to him in Wales, though I do remember he was at least languishing at a fairly low number in the 100 greatest Welshmen lists a few years back. Id have put him in the top ten. Jimmys tale is one of the most wonderful boxing stories there is.

Years ago I met a fragile old boy at a bus stop and talk got round to boxing. When we picked over some of the best, I mentioned Jimmy Wilde and he got a strange gleam in his eye and minutes later he was shuffling about telling me of how his grandfather had seen him fight in his youth, magic, boy, pure bloody magic he said, remembering his grandfathers story, and started demonstrating a few shaky punches. It was like hed dropped sixty years and was a boy again. There really is something special about boxing that ignites a fire in Welshmen that I dont think you see in any other sport, not even rugby.

I studied English and Anglo Saxon heroic literature at the University of Wales, which really made me think about boxing again a few years later. The emergence of a hero who rises against all odds is a central re-occurring theme in most folk literature. As a child I was fascinated with the stories of Greek mythology. Strength and courage are almost universally admired and usually form the main defining characteristics of a hero. It seemed to me that many of these early fighters became symbols of triumph to their countrymen for having found a way to rise above the fate that most were forced to endure.

Personally, I have always admired fighters over most athletes and sportsmen because to fight requires absolute mastery of the will. The training would be enough to level most of us. Strength and courage are not enough, while you need physical strength and stamina on a level beyond what is required in virtually any other sport, you also need an impossibly fast brain. To deal with evading blows, while trying to plant them on an opponent inside fractions of seconds is a bit like patting your head and rubbing your stomach while jogging backwards. That a boxer walks into a ring knowing that he is facing an opponent completely alone takes unbelievable self belief. Its not something that just anyone can do, let alone do well.

AmeriCymru: You have resurrected a colourful and fascinating cast of characters for a modern audience. People like William Samuels and Redmond Coleman were both working class heroes (and villains) in their day. Do you have a personal favourite?

Lawrence: Thats a really hard question, because hunting down information on some of them has been such a long and involved process. Some have grown from little more than a list of names. The characters and stories of some fighters only emerged over quite a long period of time, while many of the lesser names are more like blank canvases. Even now I have a list of fighters which I never really discovered any more about other than a name. Some still gnaw at me a little bit, one was called the Lasher which I think is a superb ring name; I just wish I knew how the Lasher earned it.

William Samuels of Swansea would probably win by a nose because you couldnt invent a character like him, and Im glad to have had the pleasure of uncovering and recording some part of his remarkable career. He was an acrobat, a strongman, and a circus performer before starting his boxing booth, and claimed the bare knuckle heavyweight championship of Wales for donkeys years. He once beat down a man who was thought to be one of the best fighters in South Wales when he was past fifty years old with one arm, after having broken the other on his opponents body. Samuels knocked them down in fairground boxing booths where hed take on all comers in towns and villages all over South Wales for twenty years and more. One of his stunts was to take on six challengers at a time, one after another. He also had the temerity to walk into a circus cage full of lions and shoot starting pistols in their faces and somehow emerged unscratched, and had enough courage to square up to John L Sullivan, the bare-knuckle champion of the world.

Samuels had a terrible temper, and fell out with almost every other Welsh boxer of his time, and became something of a celebrity in old Swansea town. I was researching him for a long time before I actually turned up a photograph of him, which was a very exciting moment, and I was pleased to see he looked just as proud and haughty as I hoped he would be. William Samuels was the first real boxing showman of any real note in South Wales. I admire his grit, and get a kick out of his contradictory nature. They say he was always laughing, good spirited, always had a penny or a peppermint to give to a child, yet he could easily blow his stack in the blink of an eye and be rolling up his sleeves moments later. He sounds like a handful, but was a man who I dont think youd forget too easily. The stories of Samuels time read quite like the film Gangs of New York, just with bare fists or gloves rather than shillelaghs or stilettos. There should really be a pub named after him in Swansea.

Redmond Coleman has always been a fascination of mine, partly because he inspired admiration and terror in almost equal measure. Redmond was locked up by the police over 120 times; hed fight anyone, anywhere, and seems to have earned his nickname of the Ironman through his willingness to fight outside the ring as well as within it. They say the only people that could keep him in line were his sister (with the aid of an iron bar she carried to beat him into line) and the local priest, who carried a stick to threaten him with one. Still, for all that he was a very hard man. Some people had suggested to me that a man like Redmond shouldnt be remembered at all, which I think is completely wrong. He was a product of the hardness of his time, where the majority slaved for a pittance and lived in abject poverty with a gloomy future stretching out before them. Redmond might have started battling on the mountainsides bare-knuckle, and with the Merthyr police force, but he also fought with gloves before Lords at the National Sporting Club in London. He was also one of the first to put his hometown of Merthyr on the map as a fighting town.

I think that being known as one of the toughest fighters around, he was targeted by a fair collection of local toughs eager to claim they had beaten the famous Ironman. He also suffers from having been recorded in works of fiction as having been the Emperor of China which was a notorious slum area of Merthyr, which is historically incorrect. Amongst the thugs, thieves, prostitutes and career criminals of China, the toughest man in the district was given the title of Emperor which would put Redmond at the top of the tree of a whole community of undesirables. In reality, China had been in decline even before Redmonds time, and he never was the Emperor of China. I think his notoriety led to his story being rolled into that of an earlier Merthyr hardman, John Jones, better known as Shoni Sguborfawr, who became notorious for his role in the Rebecca Riots, and was a much earlier Emperor of China. Redmond did serve in WW1 and appeared on a number of benefit events for Nazareth House, so he cant have been all bad.

One of the most likeable fighters in the book is probably Morgan Crowther of Newport, who I knew virtually nothing about when I began writing. He started fighting almost before he had grown out of short trousers. Although he was a small guy and didnt really have much of a telling punch, he was phenomenally durable. Morgan Crowther would think nothing of a forty round match and come up smiling. He is recorded as being a very likable and affable sort of chap, so won a lot of friends that didnt even realize he was a boxer as he didnt seem to fit the profile of a knuckle fighter. He travelled extensively to fight throughout Wales and England, and fought everywhere from a churchyard in the dead of night in Wales, through to meadows in England, racecourses, and fairgrounds as well as high end gentlemans clubs. He was an absolute pain in the neck for police forces throughout the land, who hid behind railway station walls and hedges everywhere hoping to capture him. He even got a mention in the House of Commons he became so notorious. Morgan was something of a lovable scoundrel, and was the toast of Wales among the public, probably all the more so for being hauled before the courts on a regular basis and carrying on regardless.

Having spent so much time puzzling over so many records, and trying to find pieces of information to build the story of each fighter for so long, I have to say I have a great deal of affection for all of them even some of the undesirables. Some continue to niggle away at me, because I really want to find out more about them. One of these is Robert Dunbar, who claimed the lightweight championship of Wales as well as running his own boxing booth and was a committed enemy of William Samuels. He blew out one of his eyes in a firearm accident, yet continued to fight on with just one eye for many years. I still havent found a picture or a photograph of him. Another old timer which I am very interested in is Dan Pontypridd who turned his back on prize fighting and became a preacher fighting for God rather than prize money. He even burned a belt made of gold that was given to him by his supporters after his conversion. A fascinating character and one of the earliest Welsh prize fighters to be acclaimed nationally outside Wales. I also have a great deal of respect for Ivor Thomas, who was a great fighter and was already approaching the end of his career when Jim Driscoll was the next big thing on his way up. They were friends, but Ivor had been asking him to fight for a long time before, and would always ask Jim, when be us going to have a go?. One of these days, Ivor was the usual answer. Eventually it came to pass and inevitably Driscoll was victorious. Ivors brother, Sam was also very well known, but he preferred to fight on the mountains bare fisted and was a very famous knuckle fighter in the Rhondda.

AmeriCymru: An enormous amount of research must have gone into this. What were your primary sources? Is the information presented in the book (particularly the blow by blow accounts of the many gruelling and brutal encounters between contestants) readily available to the researcher?

Lawrence: At first the book could easily have been a pamphlet. When I began researching I thought I would be able to find enough detail to just write short profiles of each fighter with a potted history of their fights. I had little hope of being able to discover much more, but it seemed pretty dry and boring. Part of the problem is that the Welsh newspapers of the time were heavily influenced by the anti-boxing nonconformist chapel folk. For this reason boxing coverage is pretty sparse in a lot of the Welsh newspapers before the turn of the century. Sometimes youre lucky just to pull up the odd paragraph, hopefully over time they stack up.

Most of the research process is hunting and cross referencing, finding contests, names, or mentions of fights and checking them against other newspapers to try and build more detail. A lot of it is list making, finding names, then trying to find dates of birth and deaths, which make for a good start, and just adding entries as you find them until you have something with a bit of meat on it. It is very time intensive, as sometimes the only thing you can do is work out when someone was active and try and trawl the newspapers. As much as anything it can be a question of working out their movements, and trying to find the various aliases they fought under, as many had pseudonyms to avoid being targeted or captured by the police. Usually you find that a bunch of them might crop up, if there was a fatality or the police captured a gang of them in the act, otherwise coverage can be extremely patchy. Some, like Morgan Crowther and Patsy Perkins got around a lot, so its a case of checking places against last known movements. Its a bit of a rabbit hole; each question you answer usually prompts ten more.

As my entries grew, and characters emerged it gave me enough hope that I might be able to write something that gave more of a flavour of their lives and times. I hadnt even considered that this might be possible when I began.

It is made more difficult because there is no central place where you can go and look at all the regional Welsh newspapers. I ended up going through microfilm in the libraries at Cardiff, Swansea, Pontypridd, Merthyr, and other places to trawl for references. Its pretty hard on the eyes, some older newspapers are in fairly rough shape, and others are only readily available on microfilm. I also travelled to London to look through the nationwide newspapers held by the British Library to follow up on those fighters that were also active outside Wales, such as Dan Pontypridd and Morgan Crowther. Some if not most of the records are far from complete, and only based on which reports could be found. I hope that in time, more information might come to light on some of them.

They do say that the National Library at Aberystwyth is currently engaged in trying to digitize every one of the Welsh 19 th century regional newspapers over the next few years, so that they are word searchable online. I think this is an amazing project, and only wish that it had been available to me when writing the book; it would have made a lot of the slog a great deal easier. I am hopeful that it will be a goldmine for any researchers engaged in Welsh history and will unearth a massive amount of information about all aspects of our history that was previously only accessible through long time consuming trawling.

I hope that I might also be able to tick off some of the many unanswered questions and more information on some of the boxers that I have researched, and some of those that have eluded me. Published boxing ring records did not really come into being until a bit later, to find the records of the earlier men you have to keep digging. I have thought it might be an idea to try and gather all the information I can find and compile a sort of mountain fighter ring record book, but I think it would probably be a fairly tough job, so maybe in the future.

It took a solid couple of years to try and find the material and then organize it so that I could fold it into coherent tales. The book probably wouldnt have happened without the enthusiasm of a large number of people; librarians throughout Wales helped me with searches and enquiries along the way, as did the Resolven Historical Society with the story of the Resolven Giant, Dai St. John. A gentleman and boxing historian by the name of Clay Moyle was also kind enough to find a number of documents and fight accounts that I would have struggled to gain access to without his help. Ivor Rees Thomas, the grandson of Ivor Thomas was also very kind in giving me further details and photographs of his grandfather for use in the book.

Really more than anyone I must thank a boxing historian named Harold Alderman from Aylesham in Kent, who received an M.B.E. for services to boxing a few years ago. We wouldnt know a fraction of what we know about many 19 th century British boxers if it wasnt for him. For years he has studied and transcribed boxing records by hand, compiling records, and adding to them and redrafting them until they become important historical records in their own right. I have never met anyone that has such an encyclopedic knowledge of any subject to the degree that Harold understands boxing, he is astonishing. I would think over the years he has worked almost round the clock to uncover the records of thousands of fighters and given his records to the descendents of old-time boxers, often without receiving a penny in return for his labour. His work has contributed the backbone of the work for a large number of boxing writers and historians for many years.

In fact, it was Mr. Alderman who compiled the record of Redmond Coleman, which made writing Redmonds tale a great deal easier. One of the great things to come out of the book was that I also tracked down Redmonds unmarked grave in Merthyr. Along with Harold and a number of the Welsh Ex-Boxers Association, we finally put up a marker, which I think was eighty years overdue.

AmeriCymru: Many of these fighters were coalminers or iron-workers. How important was their industrial background in preparing them for prize fighting?

Lawrence: I think it played a massive part in the lives of the early men of the Welsh ring, at the top end there were men who made a fair amount of money out of fighting and spent it just as easily. The majority fought for pennies, so there were very few men who could make enough money to support themselves as full-time fighters. The bulk of the population was employed in the coal and iron industries. There was always an overabundance of work, and so labour was cheap. Workers rights were non-existent, as any one that was deemed a troublemaker was easily sacked and replaced.

Coalminers started their working lives at the age of fourteen after having received a rudimentary education. There were few other opportunities on offer, so the coalmine loomed in their future even before the average pupil left school. Life was tough, hard, and in their working lives, fatalities were an inevitable part of life. It must have hardened the attitudes of the men to death and injury, and I expect most accepted the possibility of their own lives coming to an abrupt end through industrial accidents as a feature of everyday life. As the coal and iron industries grew, it brought men from all over the country and caused some tensions between natives and newcomers. Most of these disagreements were settled in the simplest way, with a fistfight. Many fights occurred in the coalmines themselves, or by an agreement to meet on the mountain.

It really is quite hard to imagine just how much frustration and anger must have built up in the men working at the coalface like beasts of burden, spending most of their lives in the dark. By the time they left the pit, I think it is fairly understandable that for many this daily frustration found an outlet in fist-fighting, drinking or both. As the popularity of the boxing booths grew, it also made financial sense for a man that was handy with his fists to seek an opportunity on the boxing booths. The better fighters might earn more in a few fights through collections and side stakes than they could earn in a number of weeks in the coalmines. For most it was probably a toss-up, spend your days working and possibly dying in the dark of the pit, or fight on the booths above ground and potentially risk the same outcome for more money.

AmeriCymru: The book, at least in part, presents a social history of an important sport that played a key role in the lives of many Welshmen in this period. Would you agree? How important was prize fighting in the lives of the ordinary collier or ironworker ?

Lawrence: That it was so widespread gives some indication of the importance to the Welshmen of the period, literally every town and village appears to have had a local champion. Some fought hundreds of times. Although it was a very brutal sport, against the backdrop of the age, fist fighting was really no worse than many other pastimes. At one time cockpits for cock fighting were a hub of activity in many villages, which is why the word survived after the cockpit disappeared, and is still in use today. Badger baiting and rat killing were common pursuits. Some of the earlier forms of combat led to horrific injuries. Shin-kicking and Lancashire wrestling often left men crippled or worse. Rightly or wrongly, in the eyes of the average collier or ironworker, a fist fight at least represented a fair stand up fight and a means of settling a problem without involving the police.

As an entertainment on the fairground, it was incredibly popular. In the days before the cinematograph and moving pictures, a boxing booth would draw vast crowds. The booths were often beautifully decorated with paintings of famous fighters doing battle, and many showmen incorporated other elements into their shows. Some featured strongmen, musical organs, beautiful girls and snake handlers. Many people saved up every penny they had for the fair, and was one of the most important social events of the calendar. Annual boxing exhibitions were one of the principal ways that Nazareth House raised money to care for the sick and the orphans in Cardiff, but it also raised funds for hospitals, Childrens Welfare Committees, and other charities. During WW1 some of the most famous boxing champions also boxed to raise funds for injured servicemen and the widows of Welsh soldiers killed in the war. Later on, into the 1930s, boxing became even more important in raising money for the soup kitchens, and feeding hungry mouths throughout periods of bitter striking.

AmeriCymru: Where can one purchase 'Mountain Fighters' online?

Lawrence: The best place to get a copy would be gwales.com , which is the website of the Welsh Book Council, who are the main distributors of the book. Some branches of Waterstones bookshops also have copies available or can order them on demand from the Welsh Book Council and there are a few other great independent Welsh bookshops that are also stocking it, including Palas Print in Caernafon ( palasprint.com ) and Browning books ( browningbooks.co.uk ) in Blaenavon. Hopefully, there should be a website in place in the not too distant future to sell the book directly alongside other titles.

AmeriCymru: What are you working on currently? What's next for Lawrence Davies?

Lawrence: Right now Im working on bringing another book into print written by Jimmy Wilde, entitled Hitting and Stopping which is very exciting. In the future I might work on a few extra projects relating to Welsh boxing, Id like to put together a website, maybe showcase a few old fighters, and pull together a few sources, try and develop a bit of interest and make the job of hunting some of this stuff down a little easier. Id quite like to do something on a bunch of the later booth boxers, like Driscoll, Welsh and Wilde and some of the many lesser known ones.

Lawrence: Right now Im working on bringing another book into print written by Jimmy Wilde, entitled Hitting and Stopping which is very exciting. In the future I might work on a few extra projects relating to Welsh boxing, Id like to put together a website, maybe showcase a few old fighters, and pull together a few sources, try and develop a bit of interest and make the job of hunting some of this stuff down a little easier. Id quite like to do something on a bunch of the later booth boxers, like Driscoll, Welsh and Wilde and some of the many lesser known ones.

Next year the World Boxing Council Convention is being held in Wales, in Cardiff, and will bring boxing superstars from all over the world to Wales. The WBC were attracted to the capital mainly due to the work of Cardiff Councillor Neil McEvoy in promoting the colourful boxing history of Wales. I think that Welsh boxing history is a really great selling point for tourism, and hope that it will tempt boxing fans round the world to come and visit. Ideally Id love to see all the strands of boxing history and knowledge pulled under one roof in a Welsh Boxing Hall of Fame. Jim Driscoll, Freddie Welsh, Jimmy Wilde and even John Graham Chambers are all inductees of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York, which is visited by thousands every year. I think a Welsh version would raise the profile of Wales and definitely help highlight our rich history in the sport. Id like to see an exhibition that includes some of the old back-timers and collect together what we know of them and display their achievements alongside some of the more famous fighters that came afterwards.

Additionally there was some talk a few years back of creating a Freddie Welsh statue at Pontypridd, which was suggested by his biographer Gareth Harris who also lives in the town. Although it received a great deal of verbal support, it never happened. As Welsh was the first boxer who really flew the flag for Wales and Pontypridd in the US, and was the first recognized World lightweight champion to have come from Wales, Id really like to see that happen. But then, if Freddie got a statue, Jimmy Wilde would have to have one too. Given that Merthyr is the only town on the globe with three boxing statues, I think it would be fantastic to build on its heritage and attract even more visitors. Two more statues wouldnt break the bank. It would be far more fitting than half the modern art rubbish that seems to get funding and has sprouted up in some towns in recent years.

I will probably start work on a new book next year which will require a fair bit of legwork, so I will be doing some head scratching over that. I have also had a few enquiries from descendents of some forgotten fighters, and am trying to assist them with uncovering more about their ancestors when I can. I might try and turn my hand to some article writing too.

AmeriCymru: Any final message for the members and readers of AmeriCymru?

Lawrence: Yes, buy my book, and if you keep it tidy, you can always re-gift it!

Its a decent size, good value for the money and itll keep a partner who is interested in boxing out of trouble for a fair while.

If you have heard that you were related to an old-time Welsh boxer or have any clippings, photographs or any other information about any of the boxers mentioned above or in the book, please get in touch via Americymru, I would be very glad to hear from you. If anyone has any information about any other mountain fighters or booth boxers not included, or that come from a later time period, I would also be interested in finding out more, in the hope of assisting with ongoing research. Thank you very much, Ceri. Cymru am byth.

A selection of related videos from the author:-

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/the-noble-art-of-self-defence - jimmy wilde clip

http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/boxing/9028282.stm - boxer remembers mountain fighting

http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/boxing/9028172.stm - boxing booths

http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/boxing/9034673.stm - billy eynon (sparring partner of Driscoll)

http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/boxing/1901448.stm - jimmy wilde audio interview

Interview by Ceri Shaw

AmeriCymru spoke with Mari Griffith author of 'The Witch of Eye' BUY THE BOOK HERE

AmeriCymru spoke with Mari Griffith author of 'The Witch of Eye' BUY THE BOOK HERE "Eleanor Cobham, the beautiful but unpopular Duchess of Gloucester, is proud of her hard-won status among the English aristocracy. She has used every trick in the book to entrap her royal husband, Humphrey of Gloucester, uncle to King Henry VI who is unmarried and childless...." read more here

AmeriCymru: A year or so ago, when we interviewed Mari Griffith on the publication of her debut novel 'Root of the Tudor Rose', she promised that Americymru readers would be among the first to know about her new novel. And are we, Mari?

Mari: Yes, absolutely! You're certainly among the first because the book has only recently been published. And, by the way, thank you for inviting me back - it's a pleasure to be here.

AmeriCymru: Now, this is your second novel, isn't it, so just before we hear all about it, can you tell us whether the first one did well?

Mari: Very well, I'm pleased to say, particularly in the US which I wasn't really expecting. But perhaps that had a little bit to do with this very web site - who knows?! And I was particularly pleased by its success because Root of the Tudor Rose was a story woven around the little-known Welsh origins of the Tudor dynasty. Essentially it was about the clandestine love affair between Catherine de Valois, the widow of King Henry V and the Welshman Owain ap Maredydd ap Tudur. I was filled with a missionary zeal to point out that the most famous dynasty in English history wasn't really 'English' at all - there was a strong element of Welsh in there, too.

AmeriCymru: And is the second book a sequel to it?

Mari: No, not exactly and neither does it have any particular Welsh flavour though it does continue the story of one or two of the characters we've already met, particularly Eleanor Cobham who became the Duchess of Gloucester during the course of the first book.

AmeriCymru: So what made you want to write this one?

Mari: Because it's such an astounding story. Let me give you a flavour of it ... and perhaps giving you the title is a good place to start. It's called The Witch of Eye and it's the story of the events leading up to the most sensational treason trial of the fifteenth century. Now, the Duke of Gloucester, who was so very nasty to Owen Tudor in the first book, is heir to the throne of his young nephew, King Henry VI. The king is a troubled teenager, spotty and a bit dim, who is by no means suited to the position he's inherited as supreme sovereign of England and France. To the Duchess of Gloucester's way of thinking, her husband, Humphrey, would make a far, far better King of England. She also realises that if anything should happen to King Henry, then her own husband would inherit the throne and she, Eleanor, would become Queen of England. A delicious prospect and she becomes obsessed with it!

AmeriCymru: Don't tell me she tried to bump him off!

Mari: Who, the King? No, not exactly, but she did gather around her a group of advisers, some of whom could interpret certain astral signs and not only read her horoscope but also tell her what the future held in store for the young King. And one of those advisers was the witch of the title - 'The Witch of Eye'.

AmeriCymru: 'Eye' as in 'I Spy'? That's an odd name.

Mari: Yes, isn't it? In fact it was the manor farm of Eye-next-Westminster, the monastic estate which belonged to Westminster Abbey and its Benedictine monastery. If you happen to be a tourist in modern-day London, it's difficult to imagine that in medieval times, a thousand acres of land to the west of the Abbey was prime farming land. It was a cattle station, too, where drovers from Wales and the West of England would take their bullocks to be fattened up before being slaughtered and sold at Smithfield Market to the townsfolk of London who had no room to farm crops and keep animals of their own. The whole of the area now occupied by Hyde Park and Mayfair to the north, right down through Belgravia to Sloane Square and Pimlico in the south, was once part of that farm. The old name of 'Eye' changed down the centuries and became Eybury and, finally, Ebury, which is now seen only in street names. One of these is Ebury Bridge Road which leads on to Buckingham Palace Road and the palace itself stands on land which was once part of the great monastic estate of Eye-next-Westminster.

AmeriCymru: So tell us more about the treason.

Mari: Well, in a sense, poor old Eleanor was more sinned against than sinning because, above all else, she wanted to be able to give her husband a son and heir so that, in the event that he did inherit the throne, at least he'd have legitimate heirs of his own. The only problem was that she sought help from Margery Jourdemayne, a so-called 'wise woman' whose husband was the yeoman-farmer in charge of the Eye estate. Eleanor consulted Margery in her desperate search for magical potions to help her conceive a child. Not such a terrible thing in itself but when the Duke's enemies got hold of the story they blew it up out of all proportion and it all got very nasty indeed. The sensational trial at which they were accused of treason against the King was the biggest cause célèbre of the fifteenth century!

AmeriCymru: Not much chance of a happy ending, then!

Mari: There is a happy ending, as it happens, but only because I invented it! It's the only part of the story which isn't absolutely based on fact. I decided to create a new character, a young Devonshire woman called Jenna, who could provide me with a positive love story which would make things turn out all right in the end. Oh, and there's a little girl in there, too, whom readers seem to dote on. She's called Kitty, or sometimes 'Kittymouse', which is Jenna's pet name for her.

AmeriCymru: It sounds as if the characters really came alive for you.

Mari: Oh, they did. It was almost as though they lived right here in the Vale of Glamorgan - around the corner from our house! I think you've got to believe in your characters before you can expect readers to enjoy your book.

AmeriCymru: Well, from what you've said about it, Mari, it sounds as though readers are already beginning to enjoy it.

Mari: It does seem that they are because it's already picked up several five star reviews. And I'm delighted at that because I've got a bad dose of 'second book syndrome' at the moment, just hoping that people will like the second book as much as they liked the first!

AmeriCymru: So, just remind us of the title again ...

Mari: The title is The Witch of Eye and it's published by Accent Press. You'll find it on Amazon as an ebook and it's out as a paperback too, so it should be available through most US bookshops and via the Americymru web site of course. And by the way, thank you for making that possible and for letting me tell you all about it. But in case anyone has any problems, I'll leave you with some links you might find helpful:

www.marigriffith.co.uk

www.accentpress.co.uk

Welsh Author Pens Australian David Copperfield Spin-off - An Interview With David Barry

By AmeriCymru, 2011-04-08

About David Barry :- David Barry (born 30 April 1943) is a Welsh author and actor. He is best known for his role as Frankie Abott, (the gum-chewing mother's boy who was convinced he was extremely tough), in the LWT sitcom Please Sir! and the spin-off series The Fenn Street Gang, He has appeared in several films, notably two TV spin-off movies - Please Sir! and George and Mildred. David is now an author with two novels and an autobiography under his belt, Each Man Kills , Flashback and Willie The Actor. Read an extract from 'Flashback' here . His next novel is about the Micawber family adventures in Australia and is called 'Mr Micawber Down Under'.

David: Having moved from Amlwch, Angelsey, to Richmond, Surrey, my parents were involved in amateur dramatics and were performing in a production of The Corn is Green. A young Welsh speaking boy was needed for the part of Idwal, which was where I came in. Another English boy was playing one of the boys in the classroom, and he attended Corona Academy Stage School. I pestered my parents to send me there, but it was a fee-paying school. But Corona assured my parents that, because I looked younger than my 12 years, they could find enough work for me to cover the fees. Which is what happened.

AmeriCymru: What was it like working with Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh?

David: Vivien Leigh spoiled me rotten, and Olivier was a remarkable stage actor. I occasionally witnessed tempestuous domestic arguments between them, and Vivien Leigh reminded me of Scarlet O'Hara.

AmeriCymru: You are best known for your role as Frankie Abbott in 'Please Sir' and 'The Fenn Street Gang'. What is your fondest recollection of working on those two series?

David: Working with a great cast, and hearing wonderful stories and memoirs from the actors who played the staff in Please, Sir! and exploring comedy in Fenn Street Gang, and starting to write scripts myself.

AmeriCymru: What, for you , is the high point of your acting career?

David: Playing First Voice in a tour of Under Milk Wood, which was not only challenging but the imagery of the words is so powerful that much of the text I can recall after more than 15 years.

AmeriCymru: In 'Flashback' you write about your childhood in North Wales, and touring to theaters in Cardiff, Swansea, Porthcawl and Llandudno. Can you tell us a little about your Welsh background?

David: My father was a London Welshman, and both my parents spoke fluent Welsh. I was born in Bangor, and my parents had a newsagent's shop, and then we moved to Amlwch. There were not many theatres around at the time, and my father loved the arts, so much of my acting inspiration came from seeing almost everything the Ritz cinema had to offer. I guess my father missed theatres, museums and galleries, as did my mother, which is why we moved close to London when I was 11.

AmeriCymru: After a long and distinguished career as an actor you decided to take up writing and published your first crime fiction novel ( 'Each Man Kills' ) in 2002. Was this a new departure for you or had you always nurtured an ambition to be a writer?

David: I began attempting to write scripts, and my first broadcast script was an episode of Fenn Street Gang. Up until that time I hadn't considered writing as an option.

AmeriCymru: Your first novel ( 'Each man Kills" 2002 ) is a detective novel set in Swansea. Care to tell us a little more about the book?

David: I was working in a summer season at Aberystwyth, and I heard a story about an armed response unit killing a murderer the previous year. The murderer committed a motiveless crime, killing a relative I was fascinated by the story, and it stayed with me over the years. I eventually considered writing a novel, and I like crime fiction. So I wrote about my antagonist being known from the start of the book, but there being no apparent motive. My protagonist's challenge is to find a motive for the crime, and I suppose the Aberystwyth incident had inspired me..I chose Swansea because of the Dylan Thomas connection, and I love the Gower peninsula and Rhosili Bay.

AmeriCymru: Your second novel ( 'Willie The Actor' 2007 ) is a novel about an ordinary man leading an extraordinary double-life of crime. We learn from the 'product description' that it is loosely based on a true story. Care to expand on that?

David: I read about Willie Sutton in a magazine article. He was a notorious bank robber with a difference - he never fought anyone or fired a shot in his life. I became fascinated by this real-life criminal who was a sympathetic character, who was such a contrast to the violent gangsters around during the prohibition era.

AmeriCymru: What's next for David Barry?

David: I love Charles Dickens's novels, and I've written a spin-off from David Copperfield. My novel is about the Micawber family adventures in Australia and is called Mr Micawber Down Under, and will be published by Robert Hale Ltd next October. I have also been working on another Swansea-based crime novel.

AmeriCymru: Any final messages for the readers and members of AmeriCymru?

David: Iechyd da i pawb!

Back to Welsh Literature page >

About David Barry :- David Barry (born 30 April 1943) is a Welsh actor. He is best known for his role as Frankie Abott, (the gum-chewing mother's boy who was convinced he was extremely tough), in the LWT sitcom Please Sir! and the spin-off series The Fenn Street Gang, He has appeared in several films, notably two TV spin-off movies - Please Sir! and George and Mildred. David is now an author with two novels and an autobiography under his belt, Each Man Kills , Flashback and Willie The Actor.

About David Barry :- David Barry (born 30 April 1943) is a Welsh actor. He is best known for his role as Frankie Abott, (the gum-chewing mother's boy who was convinced he was extremely tough), in the LWT sitcom Please Sir! and the spin-off series The Fenn Street Gang, He has appeared in several films, notably two TV spin-off movies - Please Sir! and George and Mildred. David is now an author with two novels and an autobiography under his belt, Each Man Kills , Flashback and Willie The Actor.

About Flashback :- "David Barry's autobiography spans almost five decades of theatre, film and television experience. As a 14 year old he toured Europe with Sir Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in one of the most prestigious post-war theatre tours. Vivien Leigh took a shine to him and he saw both sides of her close up. One minute she was sweetness and light, and the next she became a screaming harridan as she publicly berated Sir Laurence. In his early twenties, he starred as Frankie Abbott in the hit television sitcoms Please, Sir! and Fenn Street Gang, and those days are recounted with great humour. Hilarious events unfold as he describes working with dodgy producers and touring with argumentative actors. His is a story that covers everything from the pitfalls of working in live television to performing with hard drinking actors. 'Imagine yourself travelling - as a member of the company - with a train-load of top stars to the great cities of Europe.'" Daily Express.

Filming Owain Glyndwr ( an excerpt from 'Flashback', reproduced by kind permission of the author )

Made for television back in the 1980s, Owain, Prince of Wales, was shot back-to-back, a Welsh language version for showing on S4C, and an English version for Channel 4. The production company was English, as was the director, James Hill, and the brief they had been given by S4C was that they wanted bilingual actors who had never appeared in Pobl Y Cwm the Welsh language television soap opera. I had never appeared in the programme, and I speak a little bit of Welsh, having been brought up by fluent Welsh-speaking parents in North Wales, so my agent suggested me to the casting director who was based in London. Normally, if an actor is not known to a particular director or producer, the actor is required to interview or audition for the part. But they were finding it difficult to cast some of the smaller roles in this costume drama, because most Welsh speaking actors had presumably appeared in the Welsh soap opera at some stage. So I was accepted for the role of Second Soldier merely on the recommendation of my agent.

When the two bulky scripts dropped onto my doormat a few days later, I immediately read the English version with interest. There was no point in trying to read the Welsh version, as I had lived in England since my early teens and my Welsh was now very basic. But I knew I could cope with learning six lines, which was all my part amounted to.

I had often thought this great Welsh hero was a good subject for an exciting historical drama. But as I slowly turned the pages, mouth agape, I became more and more disappointed. Whoever had written this, or conceived of the idea, seemed to be trying to create a family adventure along the lines of the old Fifties and Sixties series Ivanhoe, William Tell and Robin Hood. There was even a corny scene in the script, straight out of a John Ford western, where the hero exits a castle on horseback, along with his sidekick Rhodri, who spots one of Henry IVs snipers up a tree, about to kill Owain with an arrow. Rhodri fires one from the hip and fells the sniping archer, whereupon our hero salutes his friend and thanks him. Diolch, Rhodri. And how do you do a John Wayne drawl in Welsh?

Halfway through the script, desperately disappointed, I gave up reading it, and only bothered reading my own characters lines. I knew this particular film was going to be a sad, bad experience, but little did I know of the farcical events that lay in store for me.

A week later I caught the Holyhead train from Euston Station, and had been instructed to get off at Llandudno Junction, where a film unit car would meet me to transport me to my hotel ready for filming on the following day. It was there I met Martin Gower, the actor who would be playing First Soldier. Our characters seemed to be the comedy relief, a sort of double-act of two inept soldiers who end up being pushed into the river by Owain and his merry men in this travesty of a historical epic.

During the drive along the beautiful Conwy Valley we got to know each other, and I discovered that Martins upbringing was similar to my own, having moved to England when he was quite young, with a Welsh tongue that was terribly rusty. But we thought we could cope with our six lines each, especially if we helped each other out in the hotel that evening.

Most of the cast and crew stayed in hotels in Betwys-y-Coed, but Martin and I were quartered in a beautiful country manor hotel at Dolwyddelan, about four miles from Betwys. As it was unusually perfect weather, we became rain cover. Most of our scenes were interiors, so we were kept on stand-by in case it should rain. It meant that in those pre mobile phone days we couldnt leave the hotel and had to hang around all day, eating and drinking. It was such a hardship, tucking into a salmon freshly caught in the nearby salmon leap by one of the waiters.

When they eventually decided to use us in a scene, we were picked up by Mr Jones the Taxi who was ferrying many of the cast here and there. As we headed for the production office at Llanrwst, where the make-up department and wardrobe were based, Mr Jones told us that he had been involved in many films, most notably The Inn of the Sixth Happiness which had been shot in the Snowdonia region, where they built an entire Chinese village on the hillside near Beddgelert. Mr Jones reminisced about the halcyon days of chauffeuring Ingrid Bergman around the Welsh mountains, when films were films and they were well organised. Not like this lot, he opined. This lot dont seem to know what they are doing.

And to prove him right, when we got to the Llanrwst production office, one of the runners was gabbling into his walkie-talkie about some lost portable toilets, which should have gone to the current location, but which had gone in the opposite direction, and loads of actors and crew were now clutching the cheeks of their backsides tightly.

When I was kitted out in my chain-mail, I went to make-up, and was reminded that perhaps I had only been cast because I fitted the brief no Pobl Y Cwm appearances and a smattering of Welsh but was actually miscast. I was supposed to be a tough soldier, one of Henry IVs mercenaries, about to rape a fair, local maiden until rescued by Owain. The make-up girl stared with concentration at my face and declared, You look like Noddy. You look so cute. How am I going to make you look tough?

I suggested a scar, but in my balaclava-like helmet there wasnt really much room left on my face. I continued to look cute.

As soon as we were ready, one of the unit cars drove us to one of the locations, the impressive Gwydir Castle, a 15th century fortified manor house less than two miles from Llanrwst. As the film had at least been blessed by sunny weather, exteriors were being filmed in the courtyard of the castle. At first glance, a film set can be misleadingly impressive in a costume drama, and you almost believe for a moment that you are stepping back in time. Until you notice all the technical paraphernalia, or an actor in doublet and hose smoking a cigarette or tucking in to a bacon butty.

As soon as we arrived on the set, we became acquainted with some of the other actors, and noticed a strange atmosphere, almost as if the cast were method actors and resented the English production company and crew. We soon discovered the reason for this when we were told by one of the actors that he had approached the director just before they were due to shoot the Welsh version of a scene, and asked if he could change a couple of lines, as they were tongue twisters. But the director, apparently pushed for time, had said dismissively that he wasnt too bothered about the Welsh version and could they just get on with it. Of course, word of this spread like wildfire throughout the cast, creating a lot of resentment. Some of the actors had re-christened the production company Mickey Llygoden Films.

When the director heard this, and asked what it meant, he wasnt pleased when he discovered Llygoden translated to mouse.

Also staying at our hotel up in the hills was Dafydd, the location caterer, with whom we drank in the evenings; which probably explains our preferential treatment on the set at lunchtimes, when we were offered a surreptitious livener in our orange juice.

Dafydd, had an assistant, Tom, who helped with the cooking in the chuck wagon. One morning I noticed Dafydd was struggling on his own. I asked him what had happened to Tom. Looking over his shoulder and lowering his voice, Dafydd replied, Tom had to go back to Caernarfon to sign on.

Outside our hotel was a small station. The railway ran from Blaenau Ffestiniog via Betwys-y-Coud to Llandudno Junction, and one night the three of us decided to go to Betwys-y-Coed by train, and drink with some of the other actors and crew at their hotel. We would have to share a taxi back, and I had Mr Joness number on a scrap of paper. Just before midnight it looked as if the bar was shutting, so I went and telephoned Mr Jones to order our taxi. His number rang and rang and rang. I thought he must have been busy working, as it was now pub turning-out time. But when I returned to the bar, and told the barman that there was no reply from Mr Jones the Taxi, he looked at his watch and said, Oh, you wont get Mr Jones now. He takes tablets.

So we walked. The following day, feeling a bit jaded, as soon as lunchtime came around, Dafydd stuck another livener in our orange juice.

I never did see the end result of our film and my tough soldier performance. But a friend saw it, and I was told I looked rather sweet.

Usually, when actors work in a large budget made-for-television film, over the years they receive small cheques for repeats or sales abroad. I dont think I ever received a residual cheque for Owain, Prince of Wales, so presumably, and deservedly, it sank without trace.

Perhaps one day some screenwriter and film company will do justice to the Owain Glyndwr story, a great tale of intrigue, politics, double-dealing, love and war. Of course, as almost everyone knows, Glyndwr vanished, and nobody knows what became of the man. It was almost as if he deliberately created his own legend status. And there is no evidence that he was betrayed or assassinated, so a film ending remains open to interpretation. Now theres an intriguing thought, and its just given me an idea!

Filming Owain Glyndwr was an extract from David Barrys autobiography Flashback, in which he writes about a childhood in North Wales, and touring to theatres in Cardiff, Swansea, Porthcawl and Llandudno. Flashback is available from www.amazon.com price $14.95.

Jan Fortune-Wood is a Welsh author and publisher. She has published four novels and is the proprietor of one of Wales' most innovative and dynamic independent publishing houses. AmeriCymru spoke to Jan about her writing and her future plans for Cinnamon Press.

AmeriCymru: You are both an author and a publisher - which came first and did one lead to the other?

AmeriCymru: You are both an author and a publisher - which came first and did one lead to the other?

Jan: Ive written all my life. My creative writing took a back seat for a long time while I was home educating my children and working (I was a Church of England minister), but I did write books on home education and alternative parenting during this time. About ten years ago i was seriously ill and we moved to North Wales. When I was beginning to recover I went back to writing poetry and had an offer from a small press to publish my first collection. A bit later I did an MA (masters degree) in novel writing and the same publisher took my first novel. By this time Id began to dabble with publishing via a small press poetry magazine and I was also realising that in my MA I particularly had editing skills that I could use so Cinnamon Press was born.

AmeriCymru: Your novel 'Standing Ground' is set in a future time dominated by the despotic E-Government. But it is replete with references to mythical Arthurian characters. Can you tell us a little more about the book?

Jan: Ive written four novels and The Standing Ground was far and away the most fun to write. It was aimed at older teenagers, but seems popular with adults too. The ideas came when home education in the UK was under attack from government moves to dictate more of the content of education at home and have more invasive policies into family life. At the time there were also wider moves to introduce ID cards for everyone which my older children were involved in opposing.

The Standing Ground imagines a not too distant future in which the benefits of technology are magnified, at least for the affluent, but the price of this is an all pervasive controlling government that no longer trusts parents to raise their own children, but instead removes them to pods attached to schools with minimal parental contact and a restricted curriculum, no history or philosophy, for example). One of the main characters is Luke, a fifteen year old who is pushing against the system, partly because he senses that his own father is different and not so tied into the system. Nazir, Lukes father, is a famous artist, but also seems to have privileges that Luke cant quite understand. Despite this connection Lukes freedom is threatened when he begins to ask too many questions and it seems likely that he will be sent to a draconian correctional facility to be made to conform.

Online Luke has met the other main character of the book, Alys. She claims to live outside of E-Government in a corner of Wales (present day Gwynedd) that has resisted and maintained a small population of free people. Luke has no idea if Alys is real or just an online fiction to trap him, but he has decide whether to take drastic action to try to reach Alys in The Standing Ground.

Alyss family have their own problems within The Standing Ground there is a fierce debate as to whether this fragile free area should use their resources to try to communicate with the wider population and break the control of E-Government (Alys and her mysterious maths mentor, Emrys Hughes, have their own project to break government encryptions) or whether they should use the European parliament to gain recognition as an independent state, giving them more security.

Ive always been fascinated by mythology and the archetypes it gives to stories. The Arthurian legends speak of Arthur returning at dark times to bring freedom and living in North Wales. The landscape is steeped in the legends of the Mabinogi, including the stories of Artur (or King Arthur). So in this story the characters slowly emerge as modern representations of those archetypes and their power of maths and technology also contains older powers that converge to stand against the darkness.

AmeriCymru: What are your future writing plans?

Jan: I have a new novel out this month, Coming Home a novel about a man who abandons one family only to later abandon another, returning to Wales to try to pick up his life and written from the perspective of himself and the women in his life.

Im currently working on two new books. The first is a poetry collection centred on a village in the mountains above my home called Cwmorthin. It was once a large slate mine with barracks and houses and chapel and mine workings, a harsh industrial place known as the slaughterhouse because of the high death rate of the miners working there, but also a thriving community with cabans in which the men met daily to discuss politics, religion, philosophy and to sing. Now it is a place of picturesque ruins and utter tranquillity, but the culture has gone. Im examining the emotional landscape of the place through natural landscape and architectural ruins in poetry sequences.

The second is a novel that deals with issues of transformation, centred on three characters who undergo major life changes in traumatic circumstances and whose stories interweave. Its set in England, Wales and Zimbabwe and covers periods from the Zimbabwean bush wars to the present day. Its involved lots of research and lots of getting to know the characters, but Im hoping the writing will come together over the next year and then the editing can begin.

AmeriCymru: When was Cinnamon Press founded and what tempted you into the publishing business?

Jan: Cinnamon Press was five years old in 2010 so were still relatively young. I was looking for a new direction after major illness and life change (I had a series of severe work place assaults in my parish work) and started a magazine to keep my brain ticking over. Then, doing the MA, I realised I had a knack for editing so Cinnamon began as a very small scale tentative project, but the success of early books helped it to snowball. We are still very much a small press and run on a shoestring with a lot of voluntary input, but the books have gone from strength to strength.

AmeriCymru: What does Cinnamon Press look for in a work for publication or an author?

Jan: Our tag line is independent, innovative, international Were really looking for distinctive voices whether in poetry or prose books that have something to say and say it with skill. We put a lot of care into editing, but we dont have the resources to take on books that are really not ready to be published so authors need to be sure the book is of high quality before they submit. In simple terms we want good writing that engages us.

AmeriCymru: In addition to publishing, Cinnamon Press provides a range of services and competitions for aspiring and established writers. Care to tell us a little more about this aspect of your work?

Jan: Its often hard to get started in writing and small presses can be good places to get that first platform. The competitions run twice a year. The novella/novel competition and the poetry collection competition are for first time authors in those genres from anywhere in the world. The competition leads to a full publishing contract for a first collection or first novel/novella and the books that have been published in this way have done very well, including being short listed for some prestigious literary prizes. The short story competition is open to any story writers and the winning story appears in an anthology named after the story along with the best runners up from the story and poetry competitions. Weve also gone on to take single author collections from two of the authors whove done well in the story competitions.

We offer other services to help writers, both beginners and more experienced writers. These include several writing courses that run through the year and a mentoring service that I run with two other Cinnamon Press writers.

AmeriCymru: Cinnamon Press also publishes Envoi magazine, can you tell our readers about that?

Jan: Envoi is the oldest poetry magazine in the UK, now in its 54th year. Its a large format, perfect bound magazine with a good range of poetry from new and established poets, reviews, articles and features such as guest poets or poetry in translation. Envoi receives an enormous amount of submissions so its very competitive to get into, but this means that the quality stays high.

AmeriCymru: Where can people buy Cinnamon Press titles online?

Jan: We have a dedicated website at www.cinnamonpress.com with all of our books available and postage rates for international customers set up there. Books are also available at www.inpressbooks.co.uk an Arts Council site promoting small press books and at the Welsh Books Council site, www.gwales.com The books are on Amazon in the UK and the Book Depository in the UK, but our own site or Gwales or Inpress are the recommended ones.

AmeriCymru: How do you see Cinnamon Press developing over the next few years?

Jan: We started with poetry collections and then added full length fiction. Over the last couple of years weve published some unique and exciting nonfiction of cross genre titles and we will be continuing to develop this area of publishing. Weve also just published our first single author short story collection and will be developing this genre further. Another new area in 2010 was a book combining poetry and imagery I Spy Pinhole Eye by Philip Gross and Simon Denison won the Wales Book of the Year award and this year we have our second imagery and poetry collaboration, a very exciting book that looks at issues of ecology, Where the Air is Rarefied by Pat Gregory and Susan Richardson. With such wonderful books my main development aim is to get the books out into more arenas these books really deserve to be read.

AmeriCymru: Any final message for the readers and members of AmeriCymru?

Jan: Welsh publishing generally exists on tiny budgets and our readers really matter. Do support the books in any way you can and if youd like to be added to our monthly mailing list with news of new books and offers send me an email jan@cinnamonpress.com

Thank you for reading and all the best for 2011.

About The Production

Producer Jon Finn noted that half of the problem is that there's never enough sunshine in Britain to have the kind of campus life those American high school movies seem to thrive on, until he and Evans started talking about the long hot summer of 1976 in the UK. They also hit upon the fact that 1976 was also a very interesting time when you started to think about it musically, and it was also an era Evans remembered well as he was at high school in Wales at the time.

"I suppose you could say the film's autobiographical for me because it's set in 1976 and that was my last year in high school. I would say it's slightly autobiographical or perhaps therapeutic for everybody who was involved. When you start work on a script like this, everyone recalls their own schooldays. We found a great quote from Cameron Crowe who said "Nothing lasts forever except for high school" and I think he's right, there's something about high school, for better or for worse, whether you had a great time or a bad time it's a period you never forget, and it's very influential on the rest of your life".

Writer Laurence Coriat who co-scripted Hunky Dory with Evans, is French, but she came over to England in 1976 as French teaching assistant and there are elements of her in the French girl who shares a house with drama teacher Viv (Minnie Driver) in the film. "It was this really hot summer and punk music was just starting, and Laurence thought England was this wonderful hot place with punk music!" explains Evans, "that was a freak summer of course but nevertheless she remembered '76 very fondly and very indelibly".

Producer Jon Finn's film production career started over 25 years ago with Working Title Films. He went on to head up the company's low budget film label WT2, and the first project they developed was the critically acclaimed and commercially successful Billy Elliot. After leaving WT2 to pursue his independent producing career, Finn met director Marc Evans and the two first collaborated on the Canadian-shot horror movie My Little Eye. Much of the following six years was taken up with musical stage version of Billy Elliot, "so this is the first film I've done since my last one with Marc, and we started taking about it back on My Little Eye".

Finn teamed up with LA-based producer Dan Lupovitz, to assist with the financing. Finn was able to utilize his experience and contacts from both the Billy Elliott film and stage musical for the whole process of putting Hunky Dory together, "For Billy, we had to find very specific kids who had a very specific skill base" explains Finn, "and we had a similar situation here. So we set up a casting department run by Jessica Ronane, as she constantly goes out and looks for kids for Billy because those kids have to be able to sing, dance and act. For Hunky Dory we wanted completely authentic kids who had to be around a certain age range". Ronane went out on the road and scoured the country, holding workshops and also searched the country for musicians to cover the orchestral work. "It was a long process, but we knew who the characters were and exactly what we needed. Aneurin Barnard we found quite quickly for Davy, and Danielle Branch to play Stella we found quite quickly as well, though finding Tom Harries for Evan took a lot longer."

"The south Wales area has produced so many amazing actors, especially around Port Talbot" explains Finn, "the last person to come out of there was Michael Sheen, and the first was probably Richard Burton. We got most of our kids from the Royal Welsh College in Cardiff which has produced this amazing crop of kids over the last couple of years. The college was incredibly supportive- both Aneurin and Danielle were there, and Tom (Harries) is just finishing and will graduate this year. South Wales seems to be slightly on fire with creativity right now."

To make the project really authentic, the production's agenda was to make everything live. As producer Dan Lupovitz explains, "we didn't want people lip-synching, so it's not just about the singing but also the playing. We constructed a forty-piece youth orchestra of high school kids playing and a chorus of twenty-six kids singing the choral parts. Joby

Talbot composed the score and Jeremy Holland-Smith arranged the music to be suitable for a high school orchestra as well as being suitable for the songs that they were arranging. So musically, we ended up with an incredibly unique blend of adolescent innocence and these very hip rock 'n' roll songs."

With such a heavily music-led project, one of the major challenges was getting clearances and permissions to use certain tracks from the 1970s. As producer Jon Finn recalls, "the permissions were really tricky and they took such a long time. David Bowie was quite quick in coming back, but we wanted to do Lou Reed's 'Venus in Furs' for this whole opening and I spent a year trying to clear those rights. In the end we just couldn't get them so we had to change the opening of the film, but that was the only one we were really defeated on."

Trying to recreate the hottest summer on record for over thirty years in Wales during the less than sweltering summer of 2010 was certainly a challenge for the production. "The schedule was insane and the pressure was on everybody and on the budget because of the weather, which kept changing so much, so the shooting schedule changed every day. Working with Marc at that point was like working with a slightly demented farmer!" laughs Finn. "I'd go and pick him up in the morning, he'd step out, and he'd go, 'the weather's going to be fine today!'. And it never was, it always rained and no matter whatever little homily he came up with about the color of the sky, it was bollocks, and it rained every day... sometimes twice a day. So, we just kept dropping scenes and rescheduling constantly. Everybody was very enthusiastic about standing in the sun, the little bit there was. There are a couple of scenes that take place in the sun that were actually shot in the pouring rain, and our director of photography Charlotte did an amazing job because I don't think you can tell!"

"The other thing about the look of the film is all to do with Marc's strengths" notes Finn. "When Marc was younger he wanted to be a painter so he approached the film from a very visual perspective- he didn't want to do any color grading in post. He wanted to set the tones the way they did in the 1970s and for that reason, we used two filters throughout, one was an antiques way and one was a low contrast filter, so it would blow the whites out slightly and saturate the oranges and make it warm. That look was planned from the start."

One of the most important locations was the lido (ed.: "lido" = a public swimming pool and surrounding facilities), because that was often ground zero for typical 70s teenage life. The opening scene that takes place there was one of the biggest challenges of all, as Finn explains: "the lido scene is at the opening of the film. The lido where we filmed was the last lido that still exists in south Wales... we found it the year before. But two weeks before filming, they closed it down because of health and safety. They drained the entire pool of something close to a million liters of water. So our location disappeared two weeks before, and we had to scramble like hell to get the location back in time. This meant meeting the local councils, as that lido was built by miners on the top of a mountain and is only used by the local community. Because it was drained, we had to try and fill the pool up, so we spoke with the water authority who told us we'd have to fill it at night because the local village would be short of water pressure otherwise."

Things went from bad to worse, as Finn recalls, "we discovered they normally fill it from the river, so we tried that but were told we needed a license so had to call a halt." Committed to filming there, production resorted to asking the local fire service to calculate how much water it would take to fill it, so they could bring huge containers of water in on trucks. To Finn's horror, it turned out that the firemen got their calculations wrong and he got a call in the middle of the night to say the pool was only half-full and they'd run out of time- and filming was scheduled for the next morning! "So, in the film, the pool's only half full of water. Every time they jump in, it's a six foot drop before you hit the water!"

The joys of filmmaking...

The Man

Peter has been invited back to America in May 2009. He will carry out a a series of poetry readings and literary talks in New York, where he will be hosted by Professor Sultan Catto of City University of New York, The Graduate Center, and his American publisher Stanley H. Barkan.

Whilst in New York he will also participate in a new project with Stanley, who is planning to produce a dvd based around the popular 'Walking Guide of Dylan Thomas's Greenwich Village' , written by Peter and Aeronwy Thomas, Dylan's daughter, which was commissioned by Catrin Brace of the Wales International Center, New York in May 2008. Peter will produce a narrative contribution and Swansea singer-songwriter Terry Clarke, a frequent participant at The Seventh Quarry/Cross-Cultural Communications Visiting Poets Events, will sing original songs and compose the incidental music.