Tagged: owain glyndwr

In The Last Days of Owain Glyndŵr , which is published this week by Y Lolfa, Gruffydd Aled Williams, a leading authority on the subject, here rigorously assesses the evidence in oral tradition, manuscripts and printed sources, as well as on the ground, sorting fact from fiction.

He also investigates Glyndŵr family history and, based on new research, brings to light new information available in English for the first time on Wales’ most enduringly inspiring national hero, who led the war of independence in the early fifteenth century.

A descendant of the Princes of Powys through his father and of the Princes of Deheubarth through his mother, Glyndŵr was proclaimed Prince of Wales in 1400, the last native-born leader to boast this title. In the first years of the century, he led a successful campaign against the English rule of Wales under Henry IV, capturing strategically-important castles and winning key battles against the English army.

However, by 1409 the castles had been retaken and the last documented sighting of Glyndŵr seems to have been in 1412. What happened to him after that and the locations of his death and subsequent burial remain shrouded in uncertainty.

‘There are certain mysteries that can never be finally solved. One such mystery is that of the last days of Owain Glyndwr,’ says Gruffydd Aled.

‘This volume, therefore, has not been written with the intention of finally revealing where Owain died or where he was buried. Its aim is rather to survey the various traditions that have been recorded about Owain’s last days in detail and to evaluate them as far as is possible in the light of known historical facts and the broader historical context,’ he added.

The author’s original Welsh language book, Dyddiau Olaf Owain Glyndŵr (2015) – the first extended and comprehensive analysis of the subject -- was hailed as ‘outstanding’ and won the 2016 Wales Book of the Year ‘Creative non-fiction’ award.

The Last Days of Owain Glyndŵr also discusses one or two new locations and traditions which have come to light since the publication of the 2015 volume, and which are significant from the point of view of tracing Owain’s last days.

The volume also includes colour photos by acclaimed photographer Iestyn Hughes.

‘It was my intention to fill a gap in Welsh historiography and to do that in as readable a manner as possible,’ added Gruffydd Aled.

Gruffydd Aled Williams grew up in Glyndyfrdwy, the district which gave Owain Glyndŵr his name. Before retiring, he lectured in Welsh at University College, Dublin and the University of Wales, Bangor, and was Professor of Welsh and Head of the Department of Welsh at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. He delivered the 2010 British Academy Sir John Rhŷs Memorial Lecture on medieval poetry associated with Owain Glyndŵr, and contributed chapters to Owain Glynd ŵ r: A Casebook (2013). He is a Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales, President of the Merioneth Historical and Record Society, and a member of Gorsedd y Beirdd (Gorsedd of the Bards).

The Last Days of Owain Glyndŵr by Gruffydd Aled Williams (£12.99, Y Lolfa) is available now.

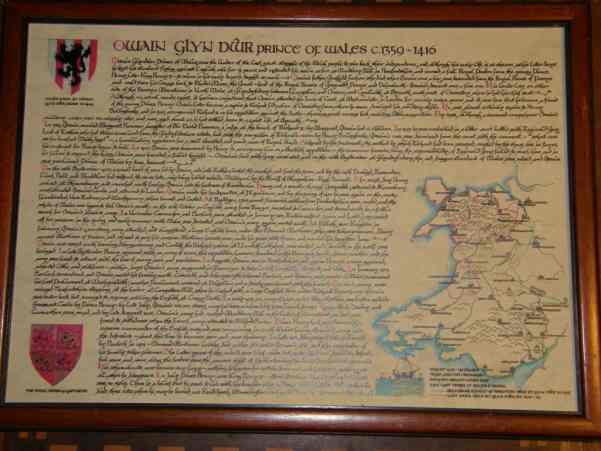

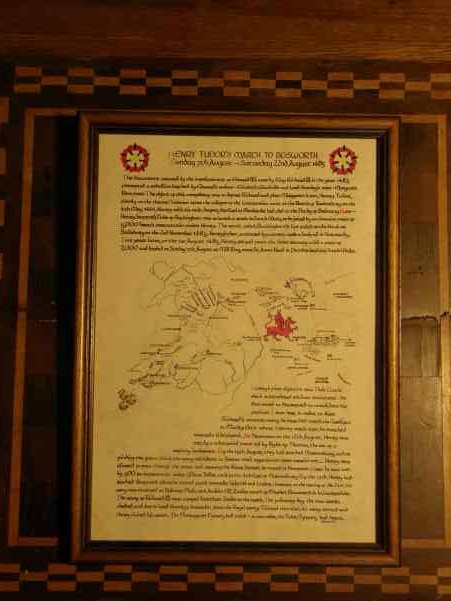

Years ago a good friend of mine went to Tenby and brought me back a gift. The two prints reproduced below have hung on my wall ever since. I dont know much about them except that they came from an antique store in Tenby and that they are not very old. They are printed on paper and mounted on masonite board. Does anyone know if they are a reproduction of anythimg interesting or significant?The text, which I may get round to copying in a future post, is for the most part historically accurate ( apart for one howler which was pointed out to me by a friend ) and of course they both reference events in the 15th century which was a very turbulent period in Welsh history. The Mab Darogan ( or Son of Prophecy ) visited Wales twice in that period. If you read the Wikipedia article ( linked above ) you will find four candidates for the title listed in all. Unfortunately they all share the same legacy of failure ( heroic and inspiring examples notwithstanding ). They all failed to create a united and independent Wales. Indeed it could be argued that Tony Blair achieved more in that direction. Does this mean that Tony Blair was the true Mab Darogan?? ( only joking )

Owain Glyndwr

Henry Tudor

Glyndŵr: To Arms! by the late Moelwyn Jones is an imaginary novel based on the real life and battles of Owain Glyndŵr. It follows the publishing of the bestselling Glyndŵr - Son of Prophecy last Christmas.

The trilogy was completed before the author’s death in 2015.

Glyndŵr: To Arms! Offers a portrayal of the life of Wales’ revolutionary hero Owain Glyndŵr, resident bard and Glyndŵr confidant Gruffudd ap Caradog tells of a time at the beginning of the 1400s when a new spirit of Welsh pride was born; when the Welsh nobility put aside their differences to unite under the banner of the Red Dragon to seek justice and self-determination.

In a vivid and vibrant account of the first two decades of the 1400s, we hear of the adventures of master bard and master lover Iolo Goch, the brutal realities of medieval warfare learned at the hands of champion axeman Einion Fwyall, and of Gruffudd's impossible love for the wife of a leader he reveres above all others.

The third and final installment will follow early next year.

Author Moelwyn Jones was raised in Bancffosfelen, Carmarthenshire, and had a career as a Welsh teacher in Cardiff before joining the BBC as an Information Officer. He then became Head of Public Relations for Wales and the Marches Postal Board and following his retirement worked in the Welsh Assembly.

‘Moelwyn had a great interest in the history of Owain Glyndŵr,’ says Delyth Jones, Moelwyn’s wife. ‘He conducted extended research into Owain’s story. He was quite the hero to Moelwyn’.

The cover art was illustrated by Machynlleth based artist Teresa Jenellen.

Glyndŵr: To Arms! by Moelwyn Jones (£7.99, Y Lolfa) is available now

Back to Welsh Literature page >

Glyndŵr: Son of Prophecy by the late Moelwyn Jones is an imaginary novel based on the real life and battles of Owain Glyndŵr.

The year is 1401, Owain Glyndŵr and his growing forces are still no more than a thorn in the side of the English crown. But when a force of some forty men succeed in taking the prestigious castle of Conwy from under the nose of King Henry IV, it marks a dramatic shift in the fortunes of Glyndŵr’s great Welsh rebellion.

The book follows a cast of vivid characters – from Rhys ap Tudur on the Welsh side to Hotspur on the English – as they dream of securing glory for their masters.

Author Moelwyn Jones was raised in Bancffosfelen, Carmarthenshire, and had a career as a Welsh teacher in Cardiff before joining the BBC as an Information Officer. He then became Head of Public Relations for Wales and the Marches Postal Board and following his retirement worked in the Welsh Assembly.

Glyndŵr: Son of Prophecy is the first in a trilogy and was completed before the author’s death in 2015.

‘Moelwyn had a great interest in the history of Owain Glyndŵr,’ says Delyth Jones, Moelwyn’s wife ‘He conducted extended research into Owain’s story. He was quite the hero to Moelwyn’.

The cover art was illustrated by Machynlleth based artist Teresa Jenellen.

The book will be launched at the Salem Chapel vestry on Market Road in Canton, Cardiff on the 24 th of October at 7pm.

Glyndŵr: Son of Prophecy by Moelwyn Jones (£6.99, Y Lolfa) is available now.

In a new novel by Peter Gordon Williams retells the compelling tale of the warrior prince and his dealings with a host of characters, ranging from his loyal bodyguard Madoc to mad King Charles of France.

The novel relates that Owain Glyn Dŵr was more than just a courageous and resourceful commander – he was an eminent scholar who, in the pursuit of learning and scholarship, looked beyond the boundaries of Wales. He devoted his life to attempting to establish Wales as an independent parliamentary democracy. His strength and sincerity shone forth in an age noted for its cynicism and corruption.

The author Peter Gordon Williams has long been enthralled with the life of Owain Glyn Dŵr and thought him a fascinating subject for a novel. Owain enjoyed many highs and endured many lows in his life and these are recalled in an engrossing and entertaining way by the author.

Peter Gordon Williams was born in Merthyr Tydfil where he attended Cyfarthfa Castle Grammar School. He graduated in mathematics from University College of Wales, Swansea and was later awarded an MSc for research. He then served for two years in the RAF before teaching in Further and Higher Education. In 1997 he retired from his post as tutor and counsellor with the Open University. He has already published three novels.

Owain Glyn Dŵr The Last Prince of Wales will be released by Y Lolfa on October the 26th, priced £7.95.

It is due to these mysteries surrounding Glyndŵr’s life that author John Hughes decided to write Glyndŵr Daughter, a fictional account of the life and times of the daughter of the Prince of Wales - Gwenllian. Although it is possible to glean Gwenllian’s renowned beauty, poise, intelligence and loyalty from poems sung by poets who visited her home in Cenarth, Llanidloes, what has not been documented is the fact that as Glyndŵr’s daughter, her life was tied to the ebb and flow of her father’s war.

In Glyndŵr’s Daughter, Hughes takes the reader back to the cloak and dagger life of the time, and shows how Gwenllian was herself drawn deeply into the murky world of espionage in order to help her father’s cause. Gwenllian suffered horrific experiences during the period of the Glyndŵr uprising, experiences which are shared for the first time in the novel.

The author also suggests a new possible burial location for Glyndŵr in the novel, and argues against the common notion that he was possibly buried close to his home, or on the estates of one of his other daughters in Herefordshire. As Gwenllian lived in a remote part of Wales, she was in a better position to help hide her father and deceive his numerous enemies during the last years of his life, and would therefore have played a crucial role in his burial. So according to John Hughes, where exactly was Owain Glyndŵr buried at dusk in the dark autumn season of 1415?

Glyndŵr’s Daughter is John Hughes’ first novel. He has a PhD in Chemistry and is a newly retired head teacher of Llanidloes High School after 26 years in office.

Extract from the novel:

They returned to Glyndŵr’s grave and stood near it for a few seconds, and Gwenllian said, “If we are successful, no one will ever know where this true prince of Wales in buried. I don’t like the thought of that…”

“Don’t worry, Gwenllian,” said Meredydd. “No one knows where Arthur is buried either, but he has not been forgotten.”

A review of Jenny Sullivans two novels Silver Fox Part 1 & 2.

Lets first look at the first of these two novels, Silver FoxThe Dragon Wakes which came off the press in 2010, The story is set in Wales during the period of Owain Glyndr and the Welsh War of Independence and although the main historical characters in this war, as we know them, have been placed as secondary to the main fictional characters portrayed in the storyline of the novel, the geographical locations and main historical events of the war, as gradually revealed via the narrative of the three principal characters Elffin, Rhiannon and Llywelyn, are as accurate as they can be from historical records available. This illustrates the outcome of intensive and thorough research into the history concerned prior to venturing on the project.

The descriptions of the battle scenes are very detailed and imaginative - especially in regards to the Bryn Gls Battle; any reader with an ounce of imagination can visualise the frenzied fighting and sprays of blood as a target was hit, and can hear the clashing of weapon upon weapon and the thundering of the horses' hooves as they charged across the battlefield.

Overall, Silver FoxThe Dragon Wakes is a novel that has been constructed and developed skilfully by a very imaginative mind. It has all the elements needed for a good historical story i.e., an unique history and setting, strong characters that have transcended time to guide us through the storyline, love, passion and a sprinkling of subtle sex.

The storyline ends in May 1403 with the burning of both Sycharth and Llys Glyndyfrdwy by the English under the young Prince Hal (Henry V) and with one of the main fictional characters, Llywelyn on his way to join Glyndr's army heading south.

The sequel, Silver FoxThe Paths Diverge follows the story from May 1403 to April 1407 with the principal Characters Elffin, Llew, Rhiannon, Siobhan, Ceridwen, Jack and Siwan finally travelling into exile to France on the ship y Groes Sanctaidd. Siobhan, Siwan and Loc were amongst a number of well constructed and interesting characters that had been introduced to this sequel which, again, has been constructed very skilfully as a continuation of what, undoubtedly, is a very interesting story based on the historical account of the Owain Glyndrs War of Independence.

But, at the end of the day, Silver Fox is a fictional story and the author is quick to admit that she has taken some liberties in the telling of the story. For example, apart from the creating of fictional characters, she has portrayed the Lady Marged (Owain Glyndrs wife) as a ruthless conniving woman who, whilst being totally loyal to Prince Owain Glyndr, would go to any lengths to ensure that her offspring were married off into the right blood lines. Shes also, in passing, portrayed Iolo Goch as a paedophile which probably wont go down well with any descendents he may have still in existence but, on the whole, the storyline is credible and evocative and presents the reader with a realistic insight into how both the peasant and 'Uchelwyr' lived, and what they wore and what they ate on a daily basis in the early 15th century.

All in all, I thoroughly enjoyed both the prequel and the sequel of Silver Fox and found it extremely difficult to put each book down once I had started reading them. This story is an excellent fictional angle on the Owain Glyndr history and very raunchy in parts especially in the prequel. I have spent more than half of my life studying and promoting the history of the Owain Glyndr War of Independence and am confident in my mind that Silver Fox part 1 and 2 could be adapted into a very interesting television series that would have worldwide appeal. I hasten to stress here that the reason I say series rather than a film (which everyone craves for) is that the storyline is based on characters associated to Prince Owain rather than on Prince Owain himself. Yes, a film on Prince Owain Glyndr and his Great War of Independence is desperately needed but, such a film will need to be a very powerful epic with Glyndr as the central figure. Such a film would be produced on the lines of Braveheart but would be even better as the Glyndr story is a much stronger one than the William Wallace story in my view.

But, whilst were waiting for someone to come up with the perfect script for a great Owain Glyndwr epic film and a major production company or a syndicate of companies that can come up with the finance to produce such a great epic, lets see if there is a production company out there with enough foresight and funding to produce Silver Fox as an interesting and unique Television series.

Sin Ifan

C.E.O. Embassy Glyndr

“If there is any subject from Welsh history which deserves to be retold, then it is the story of Owain and his revolt. I have the privilege of having been born and reared in Glyn Dŵr’s own land. In a way this volume is some small repayment for the inheritance I received in that special countryside.”

Owain was voted the most influential Welsh person of the millennium in a BBC Wales poll and revolutionaries from around the world including Fidel Castro have been influenced by his pioneering guerrilla warfare tactics. There have been petitions and internet campaigns for a Braveheart style film on Owain Glyn Dŵr, with names such as Ioan Gruffudd and Matthew Rhys being touted to play the leading role. Publishers Y Lolfa hope that this accessible book will raise the profile of Glyn Dŵr introducing one of the most inspiring stories of Welsh history to thousands of new readers. Lefi Gruffudd, chief editor and former student of R R Davies said,

“We will be sending a copy of the book to Hollywood directors as well as to Welsh film producers.”

Gerald Morgan, who translated the book from Welsh, paid tribute to the author,

“Translating this book was for me an act of pietas and tribute to the Welsh historian of my time whom I admired above all others for his extraordinary combination of a razor-sharp mind with great personal warmth.”

Owain Glyn Dŵr: Prince of Wales , Wales Book of the Month for January, is available in bookshops and www.ylolfa.com for £5.95.

Reviews of the Welsh edition:

“Readable narrative that’s more like an adventure novel than a history book.”

LORD DAFYDD ELIS-THOMAS

“Combining scholarship with accessibility, this book gives an eminently readable and inspired account of one of Wales’s most popular heroes.”

ERYN WHITE, PLANET MAGAZINE

....

About the Author

Rees Davies was a native from Cynwyd, Monmouthshire. He was educated in the Bala and at the Universities of London and Oxford, and had jobs in Swansea and London Colleges before moving to Aberystwyth as a History teacher between 1976 and 1995. Then he became a Professor in the History of the Middle Ages at the University of Oxford. He wrote several books about the history of Wales and Britain, including the lustrous English volume, The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr.

,,,

Back to Welsh Literature page >

About David Barry :- David Barry (born 30 April 1943) is a Welsh actor. He is best known for his role as Frankie Abott, (the gum-chewing mother's boy who was convinced he was extremely tough), in the LWT sitcom Please Sir! and the spin-off series The Fenn Street Gang, He has appeared in several films, notably two TV spin-off movies - Please Sir! and George and Mildred. David is now an author with two novels and an autobiography under his belt, Each Man Kills , Flashback and Willie The Actor.

About David Barry :- David Barry (born 30 April 1943) is a Welsh actor. He is best known for his role as Frankie Abott, (the gum-chewing mother's boy who was convinced he was extremely tough), in the LWT sitcom Please Sir! and the spin-off series The Fenn Street Gang, He has appeared in several films, notably two TV spin-off movies - Please Sir! and George and Mildred. David is now an author with two novels and an autobiography under his belt, Each Man Kills , Flashback and Willie The Actor.

About Flashback :- "David Barry's autobiography spans almost five decades of theatre, film and television experience. As a 14 year old he toured Europe with Sir Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in one of the most prestigious post-war theatre tours. Vivien Leigh took a shine to him and he saw both sides of her close up. One minute she was sweetness and light, and the next she became a screaming harridan as she publicly berated Sir Laurence. In his early twenties, he starred as Frankie Abbott in the hit television sitcoms Please, Sir! and Fenn Street Gang, and those days are recounted with great humour. Hilarious events unfold as he describes working with dodgy producers and touring with argumentative actors. His is a story that covers everything from the pitfalls of working in live television to performing with hard drinking actors. 'Imagine yourself travelling - as a member of the company - with a train-load of top stars to the great cities of Europe.'" Daily Express.

Filming Owain Glyndwr ( an excerpt from 'Flashback', reproduced by kind permission of the author )

Made for television back in the 1980s, Owain, Prince of Wales, was shot back-to-back, a Welsh language version for showing on S4C, and an English version for Channel 4. The production company was English, as was the director, James Hill, and the brief they had been given by S4C was that they wanted bilingual actors who had never appeared in Pobl Y Cwm the Welsh language television soap opera. I had never appeared in the programme, and I speak a little bit of Welsh, having been brought up by fluent Welsh-speaking parents in North Wales, so my agent suggested me to the casting director who was based in London. Normally, if an actor is not known to a particular director or producer, the actor is required to interview or audition for the part. But they were finding it difficult to cast some of the smaller roles in this costume drama, because most Welsh speaking actors had presumably appeared in the Welsh soap opera at some stage. So I was accepted for the role of Second Soldier merely on the recommendation of my agent.

When the two bulky scripts dropped onto my doormat a few days later, I immediately read the English version with interest. There was no point in trying to read the Welsh version, as I had lived in England since my early teens and my Welsh was now very basic. But I knew I could cope with learning six lines, which was all my part amounted to.

I had often thought this great Welsh hero was a good subject for an exciting historical drama. But as I slowly turned the pages, mouth agape, I became more and more disappointed. Whoever had written this, or conceived of the idea, seemed to be trying to create a family adventure along the lines of the old Fifties and Sixties series Ivanhoe, William Tell and Robin Hood. There was even a corny scene in the script, straight out of a John Ford western, where the hero exits a castle on horseback, along with his sidekick Rhodri, who spots one of Henry IVs snipers up a tree, about to kill Owain with an arrow. Rhodri fires one from the hip and fells the sniping archer, whereupon our hero salutes his friend and thanks him. Diolch, Rhodri. And how do you do a John Wayne drawl in Welsh?

Halfway through the script, desperately disappointed, I gave up reading it, and only bothered reading my own characters lines. I knew this particular film was going to be a sad, bad experience, but little did I know of the farcical events that lay in store for me.

A week later I caught the Holyhead train from Euston Station, and had been instructed to get off at Llandudno Junction, where a film unit car would meet me to transport me to my hotel ready for filming on the following day. It was there I met Martin Gower, the actor who would be playing First Soldier. Our characters seemed to be the comedy relief, a sort of double-act of two inept soldiers who end up being pushed into the river by Owain and his merry men in this travesty of a historical epic.

During the drive along the beautiful Conwy Valley we got to know each other, and I discovered that Martins upbringing was similar to my own, having moved to England when he was quite young, with a Welsh tongue that was terribly rusty. But we thought we could cope with our six lines each, especially if we helped each other out in the hotel that evening.

Most of the cast and crew stayed in hotels in Betwys-y-Coed, but Martin and I were quartered in a beautiful country manor hotel at Dolwyddelan, about four miles from Betwys. As it was unusually perfect weather, we became rain cover. Most of our scenes were interiors, so we were kept on stand-by in case it should rain. It meant that in those pre mobile phone days we couldnt leave the hotel and had to hang around all day, eating and drinking. It was such a hardship, tucking into a salmon freshly caught in the nearby salmon leap by one of the waiters.

When they eventually decided to use us in a scene, we were picked up by Mr Jones the Taxi who was ferrying many of the cast here and there. As we headed for the production office at Llanrwst, where the make-up department and wardrobe were based, Mr Jones told us that he had been involved in many films, most notably The Inn of the Sixth Happiness which had been shot in the Snowdonia region, where they built an entire Chinese village on the hillside near Beddgelert. Mr Jones reminisced about the halcyon days of chauffeuring Ingrid Bergman around the Welsh mountains, when films were films and they were well organised. Not like this lot, he opined. This lot dont seem to know what they are doing.

And to prove him right, when we got to the Llanrwst production office, one of the runners was gabbling into his walkie-talkie about some lost portable toilets, which should have gone to the current location, but which had gone in the opposite direction, and loads of actors and crew were now clutching the cheeks of their backsides tightly.

When I was kitted out in my chain-mail, I went to make-up, and was reminded that perhaps I had only been cast because I fitted the brief no Pobl Y Cwm appearances and a smattering of Welsh but was actually miscast. I was supposed to be a tough soldier, one of Henry IVs mercenaries, about to rape a fair, local maiden until rescued by Owain. The make-up girl stared with concentration at my face and declared, You look like Noddy. You look so cute. How am I going to make you look tough?

I suggested a scar, but in my balaclava-like helmet there wasnt really much room left on my face. I continued to look cute.

As soon as we were ready, one of the unit cars drove us to one of the locations, the impressive Gwydir Castle, a 15th century fortified manor house less than two miles from Llanrwst. As the film had at least been blessed by sunny weather, exteriors were being filmed in the courtyard of the castle. At first glance, a film set can be misleadingly impressive in a costume drama, and you almost believe for a moment that you are stepping back in time. Until you notice all the technical paraphernalia, or an actor in doublet and hose smoking a cigarette or tucking in to a bacon butty.

As soon as we arrived on the set, we became acquainted with some of the other actors, and noticed a strange atmosphere, almost as if the cast were method actors and resented the English production company and crew. We soon discovered the reason for this when we were told by one of the actors that he had approached the director just before they were due to shoot the Welsh version of a scene, and asked if he could change a couple of lines, as they were tongue twisters. But the director, apparently pushed for time, had said dismissively that he wasnt too bothered about the Welsh version and could they just get on with it. Of course, word of this spread like wildfire throughout the cast, creating a lot of resentment. Some of the actors had re-christened the production company Mickey Llygoden Films.

When the director heard this, and asked what it meant, he wasnt pleased when he discovered Llygoden translated to mouse.

Also staying at our hotel up in the hills was Dafydd, the location caterer, with whom we drank in the evenings; which probably explains our preferential treatment on the set at lunchtimes, when we were offered a surreptitious livener in our orange juice.

Dafydd, had an assistant, Tom, who helped with the cooking in the chuck wagon. One morning I noticed Dafydd was struggling on his own. I asked him what had happened to Tom. Looking over his shoulder and lowering his voice, Dafydd replied, Tom had to go back to Caernarfon to sign on.

Outside our hotel was a small station. The railway ran from Blaenau Ffestiniog via Betwys-y-Coud to Llandudno Junction, and one night the three of us decided to go to Betwys-y-Coed by train, and drink with some of the other actors and crew at their hotel. We would have to share a taxi back, and I had Mr Joness number on a scrap of paper. Just before midnight it looked as if the bar was shutting, so I went and telephoned Mr Jones to order our taxi. His number rang and rang and rang. I thought he must have been busy working, as it was now pub turning-out time. But when I returned to the bar, and told the barman that there was no reply from Mr Jones the Taxi, he looked at his watch and said, Oh, you wont get Mr Jones now. He takes tablets.

So we walked. The following day, feeling a bit jaded, as soon as lunchtime came around, Dafydd stuck another livener in our orange juice.

I never did see the end result of our film and my tough soldier performance. But a friend saw it, and I was told I looked rather sweet.

Usually, when actors work in a large budget made-for-television film, over the years they receive small cheques for repeats or sales abroad. I dont think I ever received a residual cheque for Owain, Prince of Wales, so presumably, and deservedly, it sank without trace.

Perhaps one day some screenwriter and film company will do justice to the Owain Glyndwr story, a great tale of intrigue, politics, double-dealing, love and war. Of course, as almost everyone knows, Glyndwr vanished, and nobody knows what became of the man. It was almost as if he deliberately created his own legend status. And there is no evidence that he was betrayed or assassinated, so a film ending remains open to interpretation. Now theres an intriguing thought, and its just given me an idea!

Filming Owain Glyndwr was an extract from David Barrys autobiography Flashback, in which he writes about a childhood in North Wales, and touring to theatres in Cardiff, Swansea, Porthcawl and Llandudno. Flashback is available from www.amazon.com price $14.95.

...

...

Jenny: I don’t think anyone “decides” to become a writer. One either is, or is not, and wishing can’t make it so. (I seem to meet a lot of people who “have always thought they could write a book”. My answer is usually, “then do!) The first time it entered my head was in primary school, when my beloved Miss Thomas, a spinster lady of probably quite youthful years, although she seemed ancient, of course, to an 8 year old, read one of my stories, tugged my plait and told me that if I was prepared to work very hard, one day I would become a famous writer.

I remember being quite taken with the idea, rushing home to see my poor, put-upon mother, who had five other childebeasts beside me, and reporting Miss T’s opinion. Mum put down her potato knife, sighed and said “I’m going to have to go up the school and have words with That Woman, putting stupid ideas like that in your head”.

She didn’t, however (too busy) and from that moment on I was A Writer. I wrote my first novel, aged 16, about a racial war on the Isle of Wight (go figure). That one I buried in the garden. The one after that I put in a metal wastebasket and set fire to it. Lost my eyebrows...

AmeriCymru: You are currently writing a series of historical novels based on the life of Owain Glyndwr. Care to tell us a little more about the ''Silver Fox'' series?

I did two years’ research before I wrote a word, and when the time came for me to stop researching and start writing, I just couldn’t find the “handle” into the book. So I went to that magical place, Ty Newydd, the Welsh National Writers’ Centre in Llanystumdwy, near Cricieth, David Lloyd George’s old home, leaving my family at home, and to cut a long story short, the Welsh Wizard worked his magic, and the writing began. That first book took me another two years to write and edit, and then I had to tackle the loooooong dissertation, but at last I was able to submit it (which is another tale entirely!). THEN I found out I had to have something called a “vive” or “viva” or something. Didn’t have a clue what this was until m’tutor explained. About 20 minutes of grilling, he said, do defend your novel and thesis. At that point I went into total panic.

The interview was on 12th December, my husband was working away, all my children were at work or college and I betook myself to Cardiff for the aforementioned torture session. Forty-five minutes later, a small, limp rag came out of the interview room. I was hooked into a tutor’s office, and he kept me supplied with Kleenex for the next fifteen minutes while I snotted and howled. I knew I’d totally blown it. Summoned back, the Chair of the panel said, “congratulations, Dr Sullivan”... Leaving the college, I phoned one husband, three daughters and my father-in-law. Not one of them answered. I had to wait until 7pm that night before I could tell anyone.

Then, of course, I had to write part two. Did that. Loved every moment of it, because I knew I didn’t have to submit this to anyone but a publisher. I started submitting part one, but couldn’t get any of the Welsh publishers to even read it. Historical fiction, apparently, doesn’t sell. (Tell that to Hilary Mantel.) I found a London agent who loved it, wanted to handle it, but wanted her colleague to see it first. Colleague loved it too, but “nobody’s interested in history, especially Welsh history, so we’d like you to take out most of the boring historical stuff and put in more sex...” So that was another avenue closed. I went the self-publishing route, paying for the first edition, and when that sold out I went to Amazon CreateSpace and republished in Kindle and paperback, following it up with part two. I’m currently working on part three, which I hadn’t planned, but I keep getting emails from people who want to know what happens to the characters next. I’d hoped to get away without writing the tragic end to the Glyndwr story ~ but I’m going to have to tackle it. I’ve just started research and am much cheered by the wonderful reviews the first two are getting on Amazon ~ and not all, I should add, from family and friends!

AmeriCymru: How difficult is it to imagine the world of the 15th century and in particular the life and times of Owain Glyndwr?

Jenny: Imagining the 15th century isn’t difficult. People then were just people, just as we’re people in the 21st century, with the same desires, same hopes, same frustrations, only with more blood and fewer iPads. I enjoyed writing the novels so much that, because my husband often worked away from home at that time, I sometimes used to work all day and late into the evening. It was bliss. I remember one night realising I was overdoing it, however, when I had one of my 15th century characters checking his wristwatch...

AmeriCymru: You have written many childrens books. How does writing for children and adults differ?

Jenny: That one’s easy. Adults will persevere with a book if they really want to read it. Children, if they aren’t captured in the first couple of paragraphs, will give up and go back to their X-box or Wii or whatever. I love writing for children ~ it’s pure escapism, and “I” have the most amazing adventures.

Which is why, I suppose, most of them are written in the first person. I thoroughly enjoyed writing my two historical novels, “Tirion’s Secret Journal” and “Troublesome Thomas”, both set at Llancaiach Fawr Manor near Nelson in mid-Glamorgan, and may revisit the house in Tudor times when I’ve finished part three of Silver Fox.

AmeriCymru: You have taught Creative Writing to adults and children in primary and secondary schools. Although you currently live in France you visit Wales a couple of times a year to work with school children. How important to you is this ongoing classroom contact?

Jenny: When we moved to France it was on the understanding that I could return three or four times a year. I love that contact with children, teachers, librarians, parents, and of course it helps to sell books, although that’s the least important reason of all. I love the buzz of meeting a class of children and getting ALL of them writing and achieving things they didn’t think they could. I often have teachers say at the end of a session “that boy (it’s usually a boy), I’ve never managed to get more than two lines out of him, and you’ve got a page and a half”. I’m quite smug about it, but that’s the reward ~ something they can do, that they didn’t think they could.

When I visit my daughter and her family in Northern Ireland I always visit my primary teacher son-in-law’s class and work with them. As he says, “I don’t always agree with your methods, but I admit you get results”. The other thing that arises from my school visits is that I always have an eye peeled for talent ~ if I can say to a child what dear Miss T said to me, I’m delighted, and I always offer to mentor children and young people that I meet who really want to write and are prepared to put in the necessary slog to do it. I spent the weekend talking one of my protegees out of nearly £700 worth of self-publishing (with a publishing company with a reputation like a venus fly-trap), editing a chapter for her, and recommending Lynne Truss’s “Eats, Shoots and Leaves”... Nuff said!

AmeriCymru: You have won the Tir na n–Og Award twice, once in 2006 for ''Tirion''s Secret Journal'' and again in 2012 for ''Full Moon''. How did it feel to win such a prestigious award? Can you tell us a little about the prize and the selection process?

The helicopter flight was the best fun I’ve EVER had with my clothes on...

The Tir na n-Og is chosen by librarians, who are “shadowed” by children from various schools. I don’t know any more about the process than that, but I’m glad they do it! The first time I won, in 2006, the whole thing was fairly low-key, and my overall opinion of the evening was that the Welsh language winning author was more highly regarded than the English one. The cheque for £1000 was good, though!

The 2012 award was a whole different kettle of fish ~ the Welsh award was presented on a different evening, and as well as the cheque I was given a gorgeous glass trophy, which means considerably more, given that the cheque disappeared, pided between three daughters and a husband, and there were lots of interviews from newspapers and radio and the WBC made a You Tube fillum about me, which is interesting but fairly dire from a vanity point of view. It’s a wonderful feeling to be recognised by the people who matter in literature ~ children first, then librarians and the Welsh Books Council, who organise the Tir na n-Og.

AmeriCymru: Where can people go online to buy your books?

Jenny: All my children’s books can be purchased from the Welsh Books Council on line, or from Pont/Gwasg Gomer on line, or indeed from Amazon. The “Silver Fox” books can also be obtained from Amazon, in paperback and for Kindle e-readers.

AmeriCymru: What are you reading at the moment ? Any recommendations?

Jenny: Just discovered the Kate Shugak novels by Dana Stabenow, and have read the lot. I can recommend “The Princess Bride” and anything at all by Dorothy Dunnett. I love the Jacquot books, about a French rugby-playing policeman. My favourite book of all time, however, and perhaps the book that has influenced me and my writing more than any other, is T H White’s “The Once and Future King”. It’s the story of King Arthur, and it can be read on so many different levels. Children can enjoy “The Sword in the Stone” part of it, and adults will enjoy that and the other parts two. It’s a wonderful book.

AmeriCymru: What''s next for Jenny Sullivan? Any new titles in th e pipeline?

Jenny: “Silver Fox ~ the long Amen” is being researched; I have at least five other books with Pont awaiting publication (I may get impatient and self-publish through Amazon); I’m half way through writing a fantasy for teenagers, and somewhere along the line I’m going to write a novel about two families (loosely based on mine and my husband’s) during the two World Wars, and something bloody and murderous when I can find the time. I read loads of crime fiction and want to see if I can write it too. It will be a far cry from my children’s books, but fun to write, I expect.

AmeriCymru: Any final message for the readers and members of AmeriCymru ?

Jenny: Just ~ helo, Cymru am Byth, and aren’t you glad we’re Welsh?

Interview by Ceri Shaw Ceri Shaw on Google+

LINKS

Jenny Sullivan wins 2012 Tir na n-Og award with Full Moon

Jenny Sullivan''s page on AmeriCymru

Children''s author Jenny Sullivan on basement werewolves and mad aunts

An Interview with author Charles Parry

"Owain Glyn Dwr (Shakespeare's Owen Glendower) is one of the most iconic characters in all of Welsh history. Descended from native princely stock, when an increasingly intolerable English hegemony coincided with the advent of an unpopular English king, he was the natural choice of many of his nation to lead them out of oppressive English rule. Such a leader had been foreseen by Welsh prophets for centuries as Y Mab Darogan or The Son of Prophecy."

Buy the book here:- The Last Mab Darogan

.

Charles: Thanks for inviting me to discuss the book and Glyn Dŵr. It's always a pleasure for me to do so but especially so for Americymru because I know that many of your members have a love of Welsh history and so will have at least some awareness of the Glyn Dŵr legend.

It's hard to say exactly when I became interested in him as he seeped into my soul from a young age. I was born not far from where he had lived so he’d be mentioned occasionally at school and, of course, there were hotels, streets and even railway locomotives named after him. Sometimes on days out with my family to Rhuddlan, Conway and Caernarfon castles his attacks on them were mentioned by guides – not always in complimentary terms! I remember Welsh nationalists invoking his name: I suppose it lent their campaigns a militant, anti-English air. A little later there was even a nationalist group calling themselves Y Meibion Glyn Dŵr who took to attacking English interests in Wales – mostly setting fire to holiday homes. So Glyn Dŵr wasn’t exactly seen in a good light by everyone! I have to admit that I forgot about him for a while whilst I pursued my university studies.

AmeriCymru: Many books have been written about Owain: novels, scholarly accounts etc. How does your book differ from the rest? What approach did you adopt in tackling his story?

Charles: The first book I read that seriously addressed Glyn Dŵr as an historical subject was Rees Davies’s excellent ‘The Age of Conquest’, which I read in the early 90’s. In that was a whole chapter on Owain’s revolt. It was the first balanced account that I’d read and one that saw him in a relatively positive light when shown against the oppression that the Welsh were suffering at the time. Professor Davies went on to write his classic ‘The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr’, which I read in about 1996 and I was completely entranced once again by this amazing Welsh hero. I then read dozens of other books and articles – some good, some bad – about Glyn Dŵr before deciding I should write my own.

Firstly, I wanted to write a book about him that placed his story in a wider context than all the other books I’d read. I wanted it to include, for example: how the tumultuous events in England influenced the revolt; how the situation in France affected its cause, progress and demise; how the schism in the church at the time colored it; how the Scots helped (or hindered) their Celtic cousins’ bid for freedom. It’s why the book is subtitled ‘The Life and Times of Owain Glyn Dŵr’. Secondly, I wanted it to read chronologically, rather than have chapters dedicated to particular aspects, so that the story of Glyn Dŵr unfolds in a continuous stream that takes the reader on a journey through the timeline of his revolt. Finally, I wanted it to be historically accurate and include new research that had come to light since Professor Rees’s book. Many books and articles on Glyn Dŵr unfortunately peddle myths about him and his revolt: anything written in my book as a fact is backed up with a reference supporting it. The hardback book has over a thousand footnotes and several appendices for the keener reader to explore some relevant aspects of the time in more detail, like castle warfare, arms and armor, and the anti-Welsh statutes – some of which were still in the statute books in Victorian times! It also has over 80 illustrations, including maps, almost all of which are in color. It makes for a large book (although the ebook is shorter) but to me its level of detail is a bonus. There are shorter books on Glyn Dŵr but they don’t give the whole picture and frankly many of them are under-researched and rely on hearsay.

Monument to Owain Glyndwr's Victory at Hyddgen

AmeriCymru: How important a figure is Owain Glyn Dŵr in the history of Wales?

Charles: Glyn Dŵr is an immensely important figure in the history of Wales. The revolt he led was a watershed in Welsh history. It so devastated Wales that no serious attempt to throw off the ‘Saxon Yoke’ by violent means was ever again attempted. After it many Welsh adopted English customs at home, worked in administering the country for the English, sought their fortunes in England or went fighting for the English abroad. Even the architecture of Wales, its vernacular at least, can be considered pre- and post- Glyn Dŵr as so much of it was destroyed or damaged beyond repair in the revolt – by both sides it has to be said. For much of the time after the revolt he became a symbol of the unruly Welshman: despised by the English and quietly revered by the Welsh. Since Victorian times he has become a lot more rounded as an historical figure – even the English have come to appreciate his finer qualities. I have heard people, especially Welsh people, say that Nye Bevan or Lloyd George was the greatest Welshman ever but they do not come close to having the same effect on Wales as did Glyn Dŵr: their achievements were great but they only marginally impacted on Wales; Glyn Dŵr was a Welsh leader of Welsh people in Wales and at that he was one of the greatest if not THE greatest.

AmeriCymru: Owain is famous for disappearing from history around 1410. What do you think became of him in his later years?

Charles: The greatest Glyn Dŵr conundrum is what happened to him when, as the bards said, he disappeared. After Harlech fell to Prince Hal, I believe he lived in or around his old patrimonial lands in Powys Fadog and Edeirnion where his retinue would have been most loyal. Living with one or more of his daughters on the English borders, as later local legends suggest, would have been too risky even if he were cunningly disguised as a friar or a shepherd. An interesting story in Welsh I unearthed suggested that he sailed to France to persuade Charles VI to give him some more support and died on the way but there is no other evidence for that. He most probably died around 20th September 1415. No one knows where he died or was buried but if I had to guess I would say that he died near Glyndyfrdwy and was buried in sacred ground somewhere not too far away.

AmeriCymru: What's next for Charles Parry?

Charles: I have been researching a book on John Oldcastle who as Lord Cobham became one of the first Lollard martyrs. I came across him whilst researching my book on Glyn Dŵr as he has strong ties with Wales and fought with Prince Hal. I hope to complete it this year and with luck have it published in 2016. I am also researching the death of my younger brother Ian in the 1989 Romanian revolution. As a recent S4C documentary ‘Pwy Laddodd Ian Parry?’ has discovered, it looks like it wasn’t the accident it was made out to be at the time. There might be some further developments in that this year too.

AmeriCymru: Any final message for the readers and members of AmeriCymru?

Charles: AmeriCymru is a great forum for Welsh culture and history. It’s 600 years this year since the death of Owain so I hope that AmeriCymru members commemorate him and the anniversary of his death in some small way, if only by thinking of his legacy and his contributions to Wales. Keep up the good works! Blwyddyn newydd dda i bawb.

Part 2 of an exclusive story for AmeriCymru for Glyndwr Day (September 16th). 'Glyndwr's Dream' by John Good - "The room was as described: Fine, sturdy, oak bed, large seated firedogs guarding a warm night fire, the dark cherry wood paneled walls softened with tapestries of ancient British myths and heroes......"

Glyndwr's Dream cont'd

Glyndwr's Dream cont'dThe room was as described: fine, sturdy, oak bed, large seated firedogs guarding a warm night fire, the dark cherry wood paneled walls softened with tapestries of ancient British myths and heroes. Sir John showed his guest the door–subtly anonymous, blending in with the wall panels–the door that led to the tight stone staircase that spiraled down to the dense forest close beyond. Owain, unaccustomed to such comforts, having recently found the straw mattress of a cold friar’s cell in Cardiff comparatively luxurious, sank instantly into untroubled and fathoms-deep sleep. The world and warfare, king’s pardon, parliaments and princes could all wait outside the door of this rare and serenely peaceful bedchamber.

Have you ever had a vivid dream when you knew that you were dreaming, but felt in full control? That you were an actor in and amongst the play of characters, environs and events, able to speak and clearly understand? Well, as Prince Owain’s long silver hair touched the wildflower-scented pillow, the second his eyes closed on a rare and memorable evening–the taste of full bodied red wine still on his lips–he seamlessly slipped through the door that nightly leads to life’s second self. The garden of recollections and imaginings, where deep cares and delights, fears and hopes, shadow and light, where the past present and tomorrows grow wild as blackberries in the teeming profusion of a long and late summer. Haf Bach Mihangel , the Little Summer of Michaelmas.

Owain found himself dream-walking through a series of fine, princely rooms and halls that were amalgams of real and imaginary buildings. A fusion of the family home at Sycharch, of Edward Longshank’s arrogant castle keeps, barons’ courts and knights’ fortified dwellings, all of which he had visited throughout the years; an amalgamation of a lifetime’s hallways, vestibules, galleries and even of the very room in which he now peacefully lay dreaming. The balmy air was pleasantly scented with forest flowers and herbs, and the exuberantly colored tapestries depicting ancient British heroes–struggling with dragons, Saxons, serpents, magicians, wild boars and giants–caught the eye and seemed to come alive. Almost imperceptibly, the vibrantly dyed warp and weft was slowly changing from textured threads and webs into living, breathing figures. Fifteenth century stylized bodies and faces were becoming corporeal; limbs gesturing, lips shaping sounds, growing in volume until many voices were conversing at once, as if anticipating a speaker, poet or musician.

This all seemed quite natural to our dreamer, as it would to most sleepers, and anyway, the medieval Welsh psyche was–and in many ways will always be–wide open to magical and transcendental excursion. So it was of small concern when the woven throng surged forward, into the room, forming an arc around one eminent tapestry figure who, stepping out in front of the rest, spoke directly to the prince, or rather sang in the perfect meter of Bardic lore.

“ Henffych ! Owain, shining son! As one, Avalon hails Owain.” The millennially-aged man was familiar to Owain, simultaneously being many shifting face-shapes, another amalgam, this time of real and mythologized heroes. “Yes, it’s true, Urien I am.” The golden-robed man beat his hazel staff on the floor for emphasis, as he answered this unspoken question. Owain could ask and answer by thought-words. There was no need to speak. “I am Arthur, Peredur, Pwyll; Llywelyn, Merddyn and Madog, at rest now in this westerly world. All the gathering glittering ghosts, assembled hosts of our storied history, all–as one–call this council, merge in merit, culture and heritage.” These words were a mixture of the Bronze Age Brythonic, known to the eloquent Caractâcos, the Old Welsh of Taliesin’s singing and the universally timeless symbol-sounds of dream-speech. They seemed to flow like a verdant valley’s silver nant ; a pleasantly running stream, their beauty, authority and truth filling the mind of our dreamer, by now, become a deep lake of introspective tranquility.

“Unbearably heavy heart, your life load–great weight of Wales–you carry for the Cymry yet to come. A nation’s generations in chains? Life-breath or death the decision… To submit, take the pittance of Henry’s peace, or whether never to kneel, defiant in your defeat until–not long will you wait–you sail the sea of all souls. Another brother brought home, to the solace of timelessness; I Ynys Afallon , to Avalon’s Isle.”

“Assume Henry’s amnesty? At ease under these stout eaves; a soft bed, warm fires, safe at bread; in foul weather sheltering at rest from tempestuous death blows of snowy seasons; the rest of your brightest days blessed, living free with loving family. Yet know, Prince Owain, this path has a price.”

“Wales, the Cymry , her tales and tongue, bard harping and singing, verse, chapter, banter and boast, yea! Even history’s starry astrology will vanish, banished from books. Avalon bereft of the valiant? Immortals become mortal?” The speaker’s voice rose and fell like a restless, broiling ocean, building for the storm.

“This ancient, nascent nation, beloved and bedeviled bright country, within a century will breathe her last breath; no grace will keep her from the grave. Your bowed head our kindred’s eradication. Past glories fast forgotten, each tomorrow sorrowful.”

The figure himself grew to the size of a tidal mountain, then as easily subsided to dream-normal, as the great power and visible emotion of his words threatened to carry all away. In the calm that followed, “Disregard Henry’s pardon? Head held high in defiance, the winter snow of Snowden, eira gaea’ Eryri , will bring you peace, releasing your soul to ancestral rest. No slate will mark your wintery sleep. Carrion crow will carry Owain skyward… a final scattering.”

“Many will say you died in some wide wildwood, taken in some forsaken fastness, lie cold below some lonely crag. Yet our poets–true people–harpers and tellers of tales, they will say you merely sleep; say you wait for the day of days, that you await the nation’s need. They know you’re the mab darogan , their wild-eyed prophesied son!”

A tangible, timeless silence fell, seeming to last both hours and yet no time at all. Then the speaker picked up the thread. “Many a setback, backtracking, hundreds and hundreds of indifferent, bowed years of obedience, a frail feeling, seemingly slight, still a slow tide–at its low sleep–unseen and soundlessly will rise and in rising, as weight of waters gather scorn, will grow and flow into flood and our mystic ship of dignity, our ancient nascent nation will rise high on that rising river, in your name reclaiming the realm, fighting with and righting wrongs. Cymru fydd fel Cymru fu! Cymru will be as Cymru once was.”

The speaker’s appearance, shape and size mirrored–became metaphor–for his thoughts. Speaking plainly, “Either hero of heroes, or past and last of the line, choose wisely, this is your choice, choice, choice, choice...”

These last, curt words were accompanied by the rhythmic beating of his staff on the oak floor and, as the final phrase trailed away, the tapestried throng and speaker himself lost dimension, began slipping towards grayscale, as motion turned back to motionless woolen thread. Startled, Owain burst into wakefulness, surprised to find the night had completely passed. Dawn was stealing into the bedchamber and the distant sound of someone knocking at the manor house front door brought the new day to our astonished dreamer.

Rhodri had been up for hours, attending to his countless tasks, as he had done since childhood; making sure the fires were burning brightly, the house was in order and the kitchen staff were preparing the food for the day. Hearing the knocking, he carefully unbolted and opened the heavy, front door and was just about knocked down by Maredudd, rushing past him into the hallway. “ Bore da Rhodri , good morning, are my sister and Sir John ready to receive guests yet? I need to speak to them, this moment.” Rhodri regained his balance and told Maredudd they were in the great room along the hallway, waiting for the friar to rise. Maredudd looked inquisitively at Rhodri when he mentioned the friar, but rushed on, as was ever his impetuous way, to join Alys and Sir John.

Then it was true, Maredudd had been approached under truce by Sir Gilbert Talbot, one of the kings most trusted men. He and Owain, his father, if they submitted to the king–swore never to rise again or incite the wild Welsh tribes to rise–would be pardoned; would live within the king’s peace. Maredudd didn’t seem surprised when he heard that Owain himself was asleep in the tower. They were always aware of at least general whereabouts of one another, just in case Charles the Mad–the French king–recovered his senses and decided to live up to his promise to send ships and soldiers against the English. But it wasn’t long before all three and wily Rhodri, who had immediately recognized his aging Prince, even disguised as a friar, were climbing the steep stone steps to Owain’s bedchamber.

Sir John knocked quietly at first, saying Prince Owain’s name in lowered tones, then waited. When even insistent knocking failed to bring a response, he unlatched, opened the door and went in. The room was completely empty. The fire was still embering, the bed slept in, still warm and unmade, and the door to the back staircase was wide open. The assembled company rushed through the narrow opening as one; two-at-a-time ran down the spinning back stairs, out into the bracing beauty of a clear and crisp autumn morning in the Monnow Valley.

Looking out into the ever-encroaching forest, there was not even a suggestion of a breeze to animate a turning leaf and the evocative mist had completely vanished as, apparently, had Owain ap Gruffydd Fychan ap Madog. The stillness was palpable…

No one, not even his family, would ever see the great man again. That beautiful October morning, Owain Glyndwr had quietly and unobserved walked into history without leaving a trace or even a note of farewell. There would be no eulogy or headstone when he passed and, to tell the truth, he didn’t need either. He had joined the immortals.

Deeply sad at heart, Sir John, Alys, Maredudd and Rhodri stood in complete silence for a very long time, hoping to see this enigmatic man walk back out of the woods. Then they themselves, without saying a single word, as if one, turned back to the house. As they reached the tower’s back stair, the crisp silence of the bright, new morning was broken by a solitary skylark, as it soared up, up into the clear air, singing its ecstatic praise for the day. Alys managed a bitter-sweet smile. Now she understood the meaning of her song.

Dyddiau Olaf Owain Glyndŵr / Last Days of Owain Glyndwr - New Book Launched on Glyndwr Day, September 16th

By , 2015-09-11

Owain Glyndwr’s last years are one of the biggest mysteries in Welsh history. In Dyddiau Olaf Owain Glyndwr (Last Days of Owain Glyndŵr) Gruffydd Aled Williams explores the traditions concerning the place where he died. Amongst the locations that are discussed are some that have been discovered as a result of new and exciting research by the author into manuscripts and documents; locations that could be significant but have never been discussed in print before. To support the text and to bring the possible locations to life, this attractive book is full of striking photographs by photographer Iestyn Hughes.

Gruffydd Aled Williams says, “We don’t know where Owain died, but we have traditions – the oldest of which can be traced back to the sixteenth century – which connect his death with several places in Herefordshire (where some of his daughters lived) and in Wales. This volume examines the plausibility of these traditions by looking at historical evidence (and discussing, lightheartedly on occasion, some unlikely and unbelievable places that have been suggested). Although historians, antiquarians and romantics have discussed many traditions through the ages, there has never been such extended or thorough coverage of this subject before.

Gruffydd Aled Williams’ interest in the subject began during his upbringing in Glyndyfrdwy, the area that gave Owain his name. During his professional career, his main interest was the poetry of the late 13th to early 16th century bards, known as Beirdd yr Uchelwyr, and has published a number of papers on the poems that were composed for Glyndwr and their historical background. This book is an extention of that interest, although it is an historical study rather than a literary one.

Dyddiau Olaf Owain Glyndŵr (£9.99, Y Lolfa) will be launched on Wednesday the 16th of September, in the Seddon Room, the Old College, Aberystwyth at 7:30pm, with a visual introduction by the author. There will be a warm welcome to everyone.

AmeriCymru: Was there a special reason for you to write this book?

AmeriCymru: Was there a special reason for you to write this book? Gruffydd: I was brought up in Glyndyfrdwy in the old county of Merioneth, the area which gave Owain Glyndŵr his name and where he was proclaimed Prince of Wales in September 1400. During my academic career lecturing in Welsh in universities—at Dublin, Bangor, and Aberystwyth—I specialized in the medieval Welsh poetry of the gentry ( c. 1350-1600) and became interested in the poetry addressed to Owain Glyndŵr, publishing a number of items relating to it. I delivered the British Academy’s John Rhŷs Memorial Lecture on the Glyndŵr poetry in 2010, and in 2013 I contributed two chapters to Owain Glyndŵr: A Casebook , a volume edited by two American scholars, Michael Livingston and John K. Bollard. Being conscious that 2015 marked the sexcentenary of the death of Owain Glyndŵr—there is very good evidence, on which I elaborate in the book, that he died on 21 September 1415—I was keen to ensure that the event be commemorated. Although some of the relevant material was already familiar to me, I engaged in new research on certain aspects during the two years when the volume was in preparation. Much of the research was concentrated on unpublished manuscripts and documentary sources, and I also did some field-work in Herefordshire, an area highly relevant to the topic in question.

AmeriCymru: Why, I wonder, did Owain disappear without a trace?

Gruffydd: This was a matter of necessity. After Harlech castle fell to the English in 1409 and as support for the revolt waned his situation was desperate. He was regarded by the English authorities as a traitor and essentially he was a fugitive with a price on his head. When Henry IV declared a general pardon for all his enemies in 1411 only two were excepted, Owain and Thomas Trumpington, a pretender who claimed that he was the deposed Richard II. In the words of the chronicler Adam of Usk Owain had to hide’ from the face of the king and the kingdom’.

AmeriCymru: Where did Owain Glyndŵr spend his very last days?

Gruffydd: That is the big question! We simply do not know for certain. But it is striking that many of the traditions about his last days are centred on Herefordshire where two of his daughters, Alice and Jonet, were married to local gentry, Sir John Skydmore (Scudamore) and Sir Richard Monington. In ‘The History of Owen Glendower’, a seventeenth-century work attributed to the antiquary Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt and his friend Dr Thomas Ellis, it is claimed that ‘some say he dyed at his daughter Scudamores, others, at his daughter Moningtons house. they had both harboured him in his low, forlorne condition.’ But it is worth remembering too that he had an illegitimate daughter called Gwenllian who lived in St Harmon in latter-day Radnorshire. In the book I refer to bardic evidence which obliquely locates Owain’s burial in Maelienydd (north Radnorshire). But, of course, he may have found refuge in more than one place and also with supporters who were not his kindred. As he had to keep out of the sight of the authorities his movements had to be kept secret and no definite evidence about them is available.

AmeriCymru: What did the Welsh think about Owain straight after the revolt?

Gruffydd: This is a question which defies a definite answer. There must have been much popular sympathy for him, for during his years as a fugitive he was not betrayed. But like every political figure he would inevitably have divided opinion. A sizeable number of his former supporters in south Wales enlisted in Henry V’s army which embarked on the Agincourt campaign in 1415, but some of them, it is certain, were motivated by the desire to be pardoned for their participation in the revolt. Later on in the fifteenth century there are positive references to Owain in the canu darogan , poems of political prophecy, where he is depicted as a potent military leader of the Welsh who would lead them to victory over the English. But there may also have been less positive attitudes towards him, such as those which sometimes surfaced in Tudor Wales.

AmeriCymru: Has any new evidence surfaced recently?

Gruffydd: Yes, I refer to several pieces of new evidence in my book. The most important piece of new evidence is a note which I found in one of the manuscripts of Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt. Vaughan records a piece of information he obtained from Edmwnd Prys (1543/4-1623), archdeacon of Merioneth and author of the famous Welsh Metrical Psalms, namely that Glyndŵr had been buried at ‘Cappel Kimbell’ in Herefordshire. ‘Cappel Kimbell’ was the church of Kimbolton, a tiny village some three miles from Leominster, formerly a chapelry of Leominster Priory. Edmwnd Prys was Rector of Ludlow, less than 10 miles from Kimbolton, during the 1570s, and he may well have heard some local tradition about Glyndŵr’s burial there. It is striking that that the homes of two of Glyndŵr’s daughters, Alice Skydmore and Jonet Monington, were very near (less than 10 miles) from Kimbolton. (Kentchurch Court in southern Herefordshire is usually thought of as the home of Alice and Sir John Skydmore, but I have found documentary evidence which shows that they had another home at La Verne near Bodenham in which they lived during the years of the revolt.)

AmeriCymru: Was the revolt good or bad for Wales?

Gruffydd: This is a redundant question, as the revolt did take place! It is true that the revolt would have caused suffering to many Welsh people and much economic destruction. But it was perhaps inevitable that the revolt would have happened as a reaction to the English conquest of 1282 and the civil disabilities and the psychological subjection that the Welsh suffered in its wake. There are sure signs that there were tensions in Welsh society during the fourteenth century which needed to be resolved. In the final analysis it is hardly beneficial—in any period—for a nation to be ruled by another nation!

AmeriCymru: Why is Owain Glyndŵr so important to the Welsh today?

Gruffydd: It was he who led the only significant national Welsh revolt after the English conquest.

Apart from being a brave and able military leader he had a vision for Wales as an independent state with its own institutions, its Parliament, its Church, and its universities. The memory of Owain has maintained Welsh national consciousness, thereby sustaining the continued existence of Wales as a meaningful entity. Owain continues to inspire and to sustain Welsh dreams!

AmeriCymru: Any messages for the members of AmeriCYmru?

Gruffydd: As one who can claim to be half-American—my mother was a Welshwoman who was born in Russell Gulch in Gilpin County, Colorado, where my grandfather worked in a gold mine—it is delightful to be invited to contribute to the AmeriCymru website. I wish your venture every success.

AmeriCymru: Oedd yna reswm arbennig ichi ysgrifennu’r llyfr hwn?

Gruffydd: Cefais fy magu yng Nglyndyfrdwy yn yr hen Sir Feirionnydd, yr ardal a roddodd ei enw i Owain Glyndŵr a lle cyhoeddwyd ef yn Dywysog Cymru ym Medi 1400. Yn ystod fy ngyrfa academaidd yn darlithio yn y Gymraeg mewn prifysgolion—yn Nulyn, Bangor, ac Aberystwyth—arbenigais ar ganu beirdd yr uchelwyr ( c . 1350-1600) ac ymddiddorais yn y farddoniaeth a ganwyd i Owain Glyndŵr a chyhoeddi cryn dipyn arno. Traddodais Ddarlith Goffa Syr John Rhŷs yr Academi Brydeinig yn 2010 ar y farddoniaeth i Lyndŵr, ac yn 2013 cyfrenais ddwy bennod i’r gyfrol Owain Glyndŵr: A Casebook a olygwyd gan ddau ysgolhaig Americanaidd, Michael Livingston a John K. Bollard. Gan fy mod yn ymwybodol fod 2015 yn chwechanmlwyddiant marw Owain Glyndŵr—mae tystiolaeth dda iawn iddo farw ar 21 Medi 1415, tystiolaeth yr wyf yn ymhelaethu arni yn y gyfrol—yr oeddwn yn awyddus i’r achlysur gael ei nodi. Er bod peth o’r deunydd perthnasol yn hysbys imi eisoes, fe euthum ati i ymchwilio rhai pethau o’r newydd yn ystod y ddwy flynedd pan fûm yn paratoi’r gyfrol. Canolbwyntiais lawer o’r ymchwil ar lawysgrifau a dogfennau heb eu cyhoeddi, a gwneuthum hefyd beth ymchwil yn y maes, yn enwedig yn Swydd Henffordd, ardal berthnasol iawn i bwnc y llyfr.

AmeriCymru: Pam, tybed, y diflannodd Owain heb adael unrhyw ôl?

Gruffydd: Mater o reidrwydd oedd hyn. Ar ôl cwymp castell Harlech i’r Saeson yn 1409 ac i’r gefnogaeth i’r gwrthryfel edwino yr oedd ei sefyllfa yn bur enbyd. Fe’i hystyrid gan yr awdurdodau Seisnig fel un a oedd yn euog o deyrnfradwriaeth ac yn ei hanfod yr oedd yn ffoadur a phris ar ei ben. Pan gyhoeddodd Harri IV bardwn cyffredinol i’w holl elynion yn 1411 dim ond Owain a Thomas Trumpington—ymhonnwr a hawliai mai ef oedd Rhisiart II—a eithriwyd. Yng ngeiriau’r croniclydd Adda o Frynbuga bu’n rhaid i Owain guddio ‘rhag wyneb y brenin a’r deyrnas’.

AmeriCymru: Ymhle y treuliodd Owain Glyndŵr ei ddyddiau olaf?

Gruffydd: Dyma’r cwestiwn mawr! Yn syml, ni wyddom i sicrwydd. Ond mae’n drawiadol fod llawer o’r traddodiadau ynghylch ei ddiwedd wedi eu canoli ar Swydd Henffordd, lle’r oedd dwy o’i ferched, Alys a Sioned, wedi priodi uchelwyr lleol, Syr John Skydmore (Scudamore) a Syr Richard Monington. Yn yr ‘History of Owen Glendower’, gwaith a luniwyd yn yr ail ganrif ar bymtheg ac a briodolir i Robert Vaughan o’r Hengwrt, yr hynafiaethydd enwog a’i gyfaill Dr Thomas Ellis, fe ddywedir ‘some say he dyed at his daughter Scudamores, others, at his daughter Moningtons house. they had both harboured him in his low, forlorne condition.’ Ond mae’n werth cofio hefyd am ei ferch arall—merch anghyfreithlon—o’r enw Gwenllian a oedd yn byw yn Saint Harmon yn yr hyn a ddaeth wedyn yn Sir Faesyfed. Yn y llyfr yr wyf yn cyfeirio at dystiolaeth farddol sydd fel pe bai’n awgrymu i Owain gael ei gladdu ym Maelienydd (gogledd Sir Faesyfed). Fe allai, wrth gwrs, fod wedi llochesu mewn mwy nag un lle a chyda chefnogwyr nad oeddynt yn geraint iddo. Gan fod yn rhaid iddo gadw o olwg yr awdurdodau yr oedd ei symudiadau yn gyfrinach ac nid oes unrhyw dystiolaeth bendant ar gael.

AmeriCymru: Beth feddyliai’r Cymry am Owain yn syth ar ôl y gwrthryfel?

Gruffydd: Mae hwn yn gwestiwn amhosib ei ateb yn bendant. Rhaid bod cryn gydymdeimlad poblogaidd ag ef, oherwydd ni chafodd ei fradychu yn ystod ei gyfnod ar ffo. Ond fel pob ffigur gwleidyddol diau fod mwy nag un farn yn ei gylch. Fe ymunodd cryn nifer o rai o’i hen gefnogwyr yn ne Cymru â byddin y brenin Harri V yng nghyrch Agincourt yn 1415, ond cymhellion rhai ohonynt, yn sicr, fyddai derbyn pardynau am eu rhan yn y gwrthryfel. Yn ddiweddarach yn y bymthegfed ganrif mae cyfeiriadau clodforus at Owain yn y canu darogan, lle darlunnir ef fel arweinydd milwrol ar y Cymry a fyddai’n eu harwain i fuddugoliaeth ar y Saeson. Mewn rhannau o’r gymdeithas Gymreig diau fod cof cynnes a chadarnhaol amdano fel y Cymro a arweiniodd ei genedl mewn gwrthryfel cenedlaethol yn erbyn y Saeson. Ond gall fod agwedd eraill yn llai cefnogol, fel y dengys y math o sylwadau negyddol amdano sy’n brigo i’r wyneb weithiau yng Nghymru’r unfed ganrif ar bymtheg.

AmeriCymru: A oes unrhyw dystiolaeth newydd wedi codi i’r wyneb yn ddiweddar?

Gruffydd: Oes, ac yr wyf yn cyfeirio at sawl peth newydd yn fy llyfr. Y darn pwysicaf o dystiolaeth newydd yw’r nodyn a ganfûm yn un o lawysgrifau Robert Vaughan o’r Hengwrt. Cofnoda Vaughan ddarn o wybodaeth a gafodd gan Edmwnd Prys (1543/4-1623), archddiacon Meirionnydd ac awdur y ‘Salmau Cân’ enwog, sef bod Glyndŵr wedi ei gladdu yn ‘Cappel Kimbell’ yn Swydd Henffordd. ‘Cappel Kimbell’ oedd eglwys Kimbolton, pentref bychan rhyw dair milltir o Lanllieni (Leominster), eglwys a oedd yn ‘gapel’ i Briordy Llanllieni. Fe fu Edmwnd Prys yn Rheithor Llwydlo, llai na 10 milltir o Kimbolton, yn y 1570au, ac efallai iddo glywed rhyw draddodiad lleol an gladdu Glyndŵr yno. Mae’n drawiadol fod cartrefi dwy o’i ferched, Alys Skydmore a Sioned Monington, yn agos iawn (llai na 10 milltir) o Kimbolton. (Arferir meddwl am Gwrt Llan-gain (Kentchurch Court) yn ne Swydd Henffordd fel cartref Alys a Syr John Skydmore, ond cefais hyd i dystiolaeth ddogfennol a ddangosai fod ganddynt gartref arall mewn lle o’r enw La Verne ger Bodenham y buont yn byw ynddo yn ystod cyfnod y gwrthryfel.)

AmeriCymru: A oedd y gwrthryfel yn beth da neu’n beth drwg i Gymru?

Gruffydd: Mae hwn yn gwestiwn ofer, gan fod y gwrthryfel wedi digwydd! Mae’n wir fod y gwrthryfel wedi achosi ddioddefaint i lawer o Gymry a llawer o ddinistr economaidd. Ond efallai ei bod yn anorfod y byddai’r gwrthryfel wedi digwydd fel adwaith i’r goncwest Seisnig yn 1282 a’r anfanteision sifil a’r darostyngiad seicolegol a ddioddefodd y Cymry yn sgil hynny. Mae arwyddion sicr fod tyndra yn y gymdeithas Gymreig yn ystod y bedwaredd ganrif ar ddeg a bod angen rhoi sylw iddo. Yn y pen draw, prin ei bod yn beth da—mewn unrhyw gyfnod—i genedl gael ei llywodraethu gan genedl arall!

AmeriCymru: Pam yw Owain mor bwysig i’r Cymry heddiw?

Gruffydd: Ef a arweiniodd yr unig wrthryfel cenedlaethol Cymreig arwyddocaol ar ôl y goncwest Seisnig. Ar wahân i fod yn arweinydd milwrol dewr a galluog yr oedd ganddo weledigaeth o Gymru fel gwladwriaeth annibynnol a chanddi ei sefydliadau ei hun, ei Senedd, ei Heglwys, a’i phrifysgolion. Mae’r cof amdano wedi bod yn hwb i’r ymwybyddiaeth genedlaethol Gymreig ac, yn sgil hynny, yn ateg i barhâd cenedl y Cymry fel endid ystyrlon. Mae Owain yn dal i ysbrydoli ac i gynnal breuddwydion y Cymry!

AmeriCymru: Unrhyw negeseuon i aelodau AmeriCymru?

Gruffydd: Fel un a all hawlio fy mod yn hanner Americanwr fy hunan—yr oedd fy mam yn Gymraes a aned yn Russell Gulch yn Gilpin County, Colorado, lle bu fy nhaid yn gweithio mewn pwll aur—mae’n braf iawn cael cyfrannu i wefan AmeriCymru. Pob llwyddiant i’r fenter.

AmeriCymru: Hi Tony and many thanks for agreeing to this interview. What inspires your artwork?

Tony: Since my early childhood in north Wales I spent time drawing, especially faces and animals. My late mother used to say I took after my grandfather who spent his last remaining years painting schooners and putting models of these early sailing ships into bottles. He spent his working life on these ships transporting coal from the north Wales coast (Mostyn) to Ireland.

After leaving school I attended the local college to study Art and Design and from there I furthered my studies in London. I then worked in visual communication and after working in London (there was very little opportunity in this field of work in north Wales at that time) and Ireland and for a brief period in the US (Seattle) I thankfully returned home permanently to Wales in 1989. But after being layed off work twice and unable to find suitable employment back in Wales I decided to work on my own projects. And the first project had to be about Cymru. I had bought an old print of a map of north Wales (John Speed) while I was studying in London in the early 70’s, this being something I could not resist. I have treasured this map and two years ago I carefully took it out of the frame and got it professionally scanned. This was the start of my Welsh theme, which has been a labor of love.

AmeriCymru: What is your process? How do you create these wonderful images?

Tony: All of my work is a combination of design, photography and illustration. I do the research and collect old photographs as well as taking my own photographs. I design the layout and then put everything together on the AppleMac computer.

AmeriCymru: Care to comment on the Owain Glyndwr image (reproduced above)?

Tony: The Owain Glyndwr/ Llywelyn ab Iorwerth ( Llywelyn the Great ) image is to me the most important image I have ever created. I wanted to create an iconic image that communicates a fact, a very important fact. Cut out all the bullshit. A fact that every true Welshman and women should never forget.

AmeriCymru: Where can our readers go to purchase prints? Do you supply them framed or unframed?

Tony: All my work is on the etsy site. www.etsy.com/shop/ddraigdragon

I supply them mostly unframed. (due to postage cost) I have geared a number of my artworks including the Welsh theme to accommodate the IKEA frame Virserum ( dark brown) . Overall frame size is 23 x 19 inches

(48 x 58 cm) Each individually designed limited edition print is signed and numbered.

AmeriCymru: What's next for Tony Roberts?

Tony: ddraigdragon is based in Wales and my aim/vision is to produce unique quality gifts from Wales. Categories include: Maps, Music, Illustration, Sport, and Inspirational sayings (one being) Many people will walk in and out of your life but only a true friend will leave footprints in your heart. Eleanor Roosevelt. I have also begun researching images for a general map of Ireland and Scotland.

I am listing new products on etsy.com on a daily basis.

Commissioned work is also undertaken, please email for further information.

Part 1 of an exclusive story for AmeriCymru for Glyndwr Day (September 16th). 'Glyndwr's Dream' by John Good - "It was one of those mysterious, autumn evenings that could have been painted in pastel tones of light and shade – of almost-color – by J. M. W. Turner....."

Glyndwr's Dream